Burned Out Parents Need Better Public Spaces

A Philadelphia Playstreet. Photo by Ken McFarlane/Philadelphia Parks & Recreation.

Family life has always been stressful. But a recent declaration by the US Surgeon General that parenting is a public health crisis has reignited conversations about how families might stop the endless spiral of expectation. What’s been less discussed is how the physical design of housing, transportation and public space makes life harder by increasing commute times, reducing communal play spaces and creating barriers to children’s mobility.

Parenting experts say children need to learn independence and resilience. But cities and suburbs don’t offer safe pedestrian and bike routes to school, malls kick teenagers out on the weekends, and free time disappears under a spreadsheet of activities. All of those “musts” take more of the parents’ time or money to navigate, because the child can’t do it on their own.

As Darby Saxbe, a clinical psychologist, recently wrote in the New York Times, “underparenting requires structural change.” Unlike most political pundits, she’s not just talking about economic policies like family leave and subsidized child care. She’s talking about actual physical structures, and the cultural change required to populate them. We need to “build back our tolerance for children in public spaces,” she writes, “and create safe environments where lightly supervised kids can roam freely.”

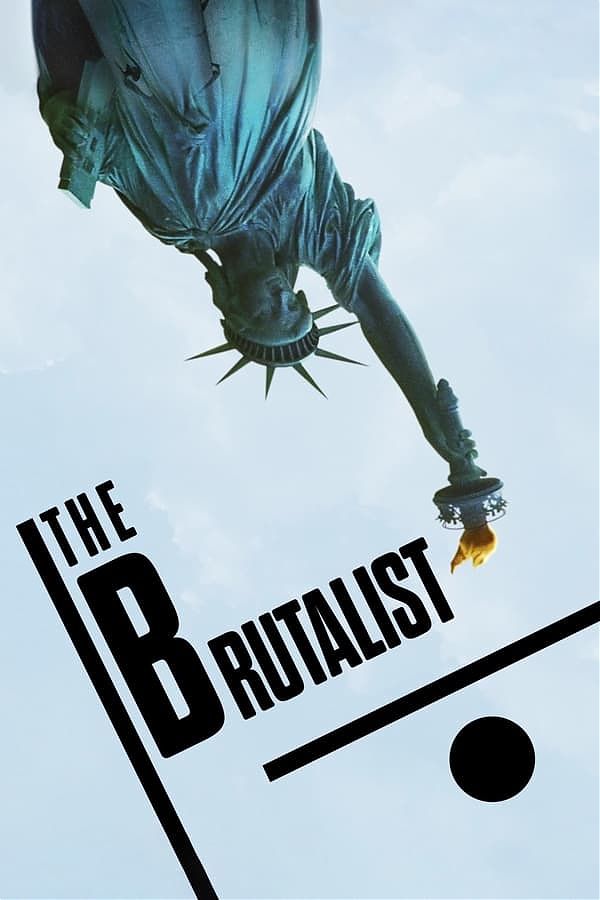

Why 'The Brutalist' Is a Terrible Movie

Architecture and culture writers Mark Lamster, Alexandra Lange and Carolina A. Miranda get together to put a spike into Brady Corbet’s architectural magnum opus, “The Brutalist.” Spoiler alert: this is one big spoiler.

You Turned a Mall Into Housing?

Interview with Anjulie Rao about the feasibility of turning malls into housing.

As strange as a recent viral project in Milwaukee may seem, there’s a historical precedent for this kind of adaptive reuse—but that doesn’t mean it’s always done right.

If you’re of the Gen X or millennial generations, chances are, much of your youth was spent at the mall: buying Beanie Babies at Scoops!, eating at the food court, or accompanying your parents to Sears. For nearly 70 years, shopping malls were an important part of community life in many cities and suburbs—yet, of around 2,500 malls that existed in 1980, only 700 remained as of 2023, according to commercial real estate analytics company CoStar. For many Americans, this means central places of gathering and commerce have declined to the point where their abandoned interiors have made for excellent ruin porn.

But these massive structures are also seeing a rebirth as a much-needed entity: housing.

The Rainbow Connection

Hoover Elementary School in Oakland, CA. Photo by Marissa Leshnov

The minds of children are particularly receptive to color; the rainbow is one of the first vocabularies that they learn, and the hues allow them to absorb concepts easily—without losing emotional power. Laura Guido-Clark’s understanding of that power solidified when she saw The Wizard of Oz at the age of 10. “I realized that Oz was supercharged; it was full of hope and joy and wonder…” she trails off. “Films have such a short time to tell a story, and the fact that color was connected to story was a big part of their appeal for me.”

Connecting color to story became her mission, first as a textile designer, and subsequently as a color consultant and developer of the Love Good Color system, a methodology developed to help companies identify what they want out of their products’ palette. One of Guido-Clark’s major successes is Herman Miller’s Cosm Chair, for which she designed and curated three unusual, yet universally appealing hues. Typically, people browse the eclectic colors for big furniture purchases, and then pick standard navy blue, beige, and burgundy for their final selections, but with the Cosm, “People were ordering colors like they were ordering neutrals,” she says.

The Answer To Making Cities More Family-Friendly? Courtyards

An interior courtyard at Sunnyside Garden Apartments. Photo Jeenah Moon/Bloomberg.

The population of children under five is shrinking across the US. That group has decreased most rapidly in big cities: 14% in Los Angeles County, 18% percent in New York City and 15% percent in Cook County, Illinois, which includes Chicago.

This is bad news for the diversity and stability of cities, which are improved by the amenities that families seek — parks, public libraries, safe streets. It’s also discouraging for families who prefer to live in the city or don’t have the option or desire to move to the car-dominated suburbs. Any effort to retain families has to start with housing, their primary expense.

That one weird trick for making cities more family-friendly? We’ve known it for decades: It’s the courtyard.

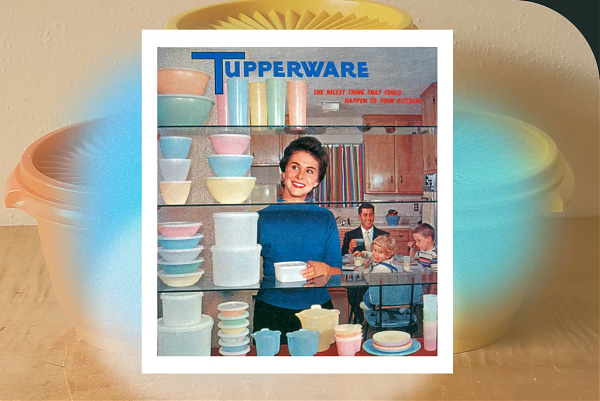

Tupperware days

In 1970s Cambridge, grain salads and hummus abounded. I carried my lunch in a gray plastic Thermos lunchpail big enough to corral my daily array of tiny orange Tupperwares. Even today, a sandwich is my lunch of last resort.

So strong is my identification with Tupperware that I even made it into a verb: To Tupp, i.e. “Let me Tupp the leftovers.” (And yes, I do know this is slang for something else in Britain.)

While a few of those one-serving Tupperware cups are still floating around my family’s cupboards, I may not be able to Tupp much longer: Tupperware Brands filed for bankruptcy protection in September, “succumbing to mounting losses due to poor demand for its once popular colorful food storage containers,” according to Reuters.

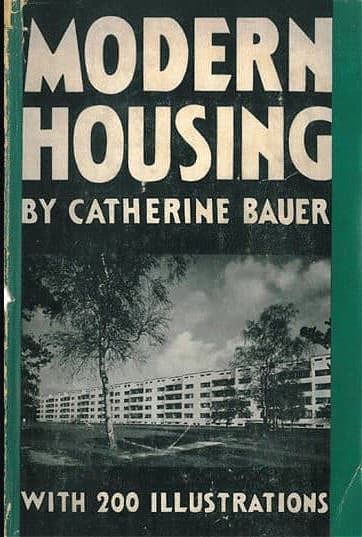

Catherine Bauer Wurster: A Thoroughly Modern Woman

The latest episode of New Angle: Voice features the first lady of American housing policy.

Catherine Bauer’s life divided into two names and two geographies: her urban east coast youth and her Bay Area soft landing. She hobnobbed with the bohemian elite of the interwar years, charming the pants off of the big architecture names of the Weimar Republic, Paris cafe society, and the International Style: Gropius, Mies, Corb, Oud, May — with her lover, Lewis Mumford — culminating in the publication of her 1934 classic: Modern Housing.

Her glamour and charismatic presence endeared her to trade unionists, labor leaders, and politicians, including five presidents — who she tried to turn to her vision of housing as a worthy responsibility of the government — sexier and leftier during the Depression. Her arguments were a harder sell in the red scare fifties and ran into a “dreary deadlock” in the suburban sixties. In the Bay Area she developed an academic career that also included architect husband William Wurster, a daughter, and a house on the bay — all surrounded by the nature she quickly grew to love. Her legacy lives on to this day, as even the latest of housing legislation echoes the progressive ideals she was advocating for in her prime.

Forever towels

The chic durability of 100% linen.

My late grandmother’s house comes with forever things. A dark-stained oval dining table, a Cosanti bell, nesting phoebes, and a drawer full of tea towels. On some, the original design is faded into oblivion, leaving faint organic lines across the woven fabric. Others proudly display the calendar for 1995 under the bright silhouette of a chicken, the alphabet in flowers (H is for Hyacinth, I is for Iris), a William Morris print.

In the drawer they seem depleted. Hung on the hook by the sink, or draped over the oven door handle to dry, they are limp. These are not the dish towels of kitchen renovation dreams, casually draped over a farmhouse sink, or the kitchen towels of influencer Instagram, folded in fat packages into an under-sink caddy.

And yet, as I wiped dinner dishes or spread out blueberries to dry, they proved there was still life in these natural fibers. Every towel worked better than the new ones I had at home, purchased on the recommendation of one of the perpetual recommendation engines. The contemporary towels were thick, were looped, were two-sided, and were made of natural fibers. But as I approached them with dripping hands, their smooth surfaces seemed to shy away from the work. Those Williams-Sonoma waffle towels? The Wirecutter pick? They refused to absorb.

An Artist Reimagines the Spaces of Childhood, With Thorny Results

Hugh Hayden’s “Brier Patch” (2022). Yasunori Matsui / Madison Square Park Conservancy.

The first time Hugh Hayden tried to build a playground, his client said no. The sculptor’s pitch to the nonprofit Public Art Fund included a full-size play structure made of wood and covered in thorns. The curators got the point of the piece, titled “America.” The problem was that the prickly playground would have to be fenced off.

The piece Hayden ultimately made had an equally thorny backstory, but a smoother shell. “Gulf Stream” is a beautifully crafted oak rowboat that, upon approach, reveals itself to have the frame of an enormous ribcage — as if Jonah’s boat and Jonah’s whale had merged into one uncanny object. Hayden drew on references from art history, namely Winslow Homer’s painting of a Black man alone in a boat in shark-infested waters and Kerry James Marshall’s depiction of a more idyllic version of the same. Kids got it right away.

“We had no idea how popular it would be as a playground,” Hayden says. “Literally within 30 seconds that we installed it, children ran up and parents started taking their photos with children climbing on it.”

Lesson learned: Put a climbable structure in a park and it’s gonna get climbed.

On X

Follow @LangeAlexandraOn Instagram

Featured articles

CityLab

New York Times

New Angle: Voice

Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness