Instagram Archi-tourism

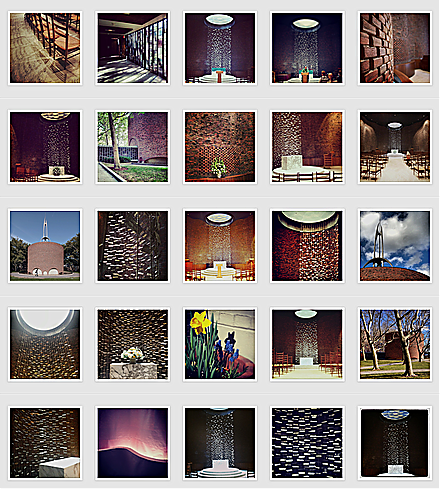

Instagram hashtag search for #MITchapel

From May 28 to May 30, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis will host the symposium Superscript: Arts Journalism and Criticism in the Digital Age. Since I could not participate in person, the organizers asked me to contribute to the Superscript Reader, an online adjunct to the talks (which will all be livestreamed) at the symposium.

When I’m invited somewhere new, the first thing I do is go to Google and type in “[city name] modern architecture.” Mexico City, San Francisco, Sarasota. It’s a way to structure my time and a quick aide-memoire. Some cities I don’t even have to Google. Mention Detroit and I’ll say generalmotorstechnicalcentercranbrookmiesatlafayetteparkandthatprettyyamasakiatwaynestate.

Portland? Halprinopenspacesequencethemichaelgravesportlandbuildingisrightnextdoor. The drive to Alvar Aalto’s Mount Angel Library is worth it, I might add.

Boston?

Saarinenchapelatmitgropiushousecarpentercenterandofcoursepaulrudolphatgovernmentcenter. Pause for breath. Brandeis has a great postwar architecture collection also.

From my vantage point in Brooklyn I visualize the map of the United States not as foreshortened, as in the great Saul Steinberg New Yorker cover, a poster of which hung in my childhood breakfast nook, but as a dark space filled with twinkling lights. Some of those lights are big cities like Chicago and Los Angeles, but many of them are stars only of the slide room in which, in college, I used to file images from art history lectures. Bartlesville. Eureka Springs. Moline. In many cases I learned to put them in alphabetical order before I’d seen the pictures on the screen. These were and are the all-star towns in the modern architecture firmament, still absent from the typical tourist map. We have the tools to make our own maps now, but they haven’t yet reached the design heights of the subject matter.

When I made my pilgrimage to these last three places in 2003 (home of, respectively, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Price Tower, E. Fay Jones’s Thorncrown Chapel, Eero Saarinen’s Deere & Co. headquarters) there was no Instagram. I took a few awkward photos, stored the feeling of those places in my memory, and moved on. If I went back today, the locations would be the same; my ability to make that map light up for you would be different. I would store that same feeling in my memory, but I would also be telling my followers about the experience in real time, taking tens of photos, posting one, two, three on Instagram, using social media to make these places light up for you, too. But once I am back home, I want to save that trip for your future trip. When you type in “[city name] modern architecture” what you could get is not a mess of ArchDaily links but a path that joins the new version of those old slides to a map and directions so that you can recreate that experience, not just follow along from your desk.

In a 2011 essay on the future of the Built Works Registry, Aaron Straup Cope and Christine Kuan describe buildings as “the setting for and the cast of secondary characters—the soundtrack music—that inhabit our histories.” It is the ongoing work of the architecture critic to make those secondary characters the main event, the stars, and to help onlookers to see how that soundtrack affects your mood, how that music changed your path. Sometimes—as with travel—the work of the critic is not to criticize but to wave her hands with enthusiasm. Visuals show, not tell, why it might be worth it to make the drive north from Tulsa to Bartlesville, or how much Knausgaard missed by only visiting a bowling alley and ruin-porn-cliché “ghostly blocks” in Detroit. Visiting older architecture is an essential part of the job, even though it is usually unpaid. Having Instagram by my side makes me feel like I’m exploring with friends, even if I’m stealing time from a work trip and often alone. That sense of immediacy, essential to Instagram’s appeal, transforms old structures into new discoveries. The question is how to keep that contagious energy as you make snaps into an archive.

There are organizations that make architecture maps for you, with the Walker’s own Minnesota By Design site as one of the latest and best examples. As the website says, “the project seeks to increase public awareness of the human-built world in Minnesota—its landscapes, buildings, products, and graphics, both past and present.” Minnesota By Design’s innovation is adding sites of creation, as well as multiple design disciplines, to a single map. It also adds an interactive element, as visitors can nominate their own examples, adding to a museum collection without financial outlay. On an idea Instagram trip, the same thing can happen to you, as followers suggest other landmarks your pre-trip Google may have missed, changing your itinerary in real space and real time.

Smart preservation organizations also make their own tour booklets—and, now, apps—to guide you through their cities’ architectural high points. The Cultural Landscape Foundation’s What’s Out There guides to Washington, Denver and (coming soon) Toronto focus on the landscape architecture of cities, an even less noticed and noted soundtrack than architecture. When I travel with the kids, landscape architecture takes up an ever-increasing percentage of my archi-tourism time. For the wiggly outdoor > indoor, parks > private homes.

But not every town, or every nonprofit, is that organized. Not every town has the critical mass for a non-profit. There should be a simpler way for anyone to save trips, one that saves that sense of discovery even as it creates an archive. Archi-tourism is a web community waiting for its own digital address. There are already versions of this. Jauntful was recommended, but I found the map-to-photos connection hard to make, and it lacks directions; in addition, because it is based on the Foursquare platform, it privileges restaurants and shops over their built envelopes. Who wants to figure out what business is occupying that famous atrium now? Roadtrippers is better on directions, but I suspect their definition of “attraction” is somewhat different than mine—though I could use architecture-adjacent restaurant suggestions. Curbed does architecture maps with links to building websites, plotted on a real map, that are helpful for trip planning, but you would still have to translate them into another form to use while traveling. What I want is the combination of Instagram, Google Maps, and AAA’s TripTiks, the spiral-bound paper kind, which I remember with fondness from a family cross-country trip in a conversion van. I can’t make it myself, so let me offer a roadmap for a possible digital experience.

This summer, I’m headed to Buffalo, home of the Albright-Knox Museum, the Kleinhans Music Hall, and a high number of other modern architecture and landscape treasures. While I’m on the road, I’ll Instagram each in turn, posting (as I try to do) with architect, building title, and date as I go. I’ll even geotag for posterity. After the trip, I’d like to go to my dream site—Archimaps, Designtrip, whatever—and open and label a new map. I could drag and drop (or copy the URL of) one Instagram of each structure onto a simplified map of Buffalo, and the site would place them, with a thumbnail image, in their proper geographic relationship. This visual shorthand is missing from many existing map sites, but for buildings, the picture is a much easier trigger than a name. Buttons at the top would allow me to interact with my collection four ways: as a map with the information at the site, rather than in a separate keyed list; as a grid of thumbnail images, displaying the information on each Instagram plus the street address; as a compact text-only list; and lastly as a trip, with the option to choose directions for car, transit or walking from point to point. I should then be able to download this information to an app on my phone, share the link with someone else, make it public on the site, or print out any of the screen versions—including an illustrated TripTik to put in my purse.

Just as I’m trying to avoid the mess of DIY mapping at home for every new trip—and to help others to avoid the same—I’m trying to avoid the sweaty situation on the ground of having to look up each building on a list in turn, and realizing, later in the day, you’ve missed something that was only a few blocks away three hours ago. (Archi-rage.) Or having to Google image search on your phone to remember what the name on your list looked like and why you wanted to see it in the first place. (Archi-amnesia.) Or having to choose between using your phone’s camera and your phone’s GPS, as your power slowly ebbs. Or making up a blog post, like this one, that has the photos and the commentary but still requires readers to re-map it themselves. Why make both traveler and mapper reinvent the wheel each time? If it were this easy I would make different versions, adult-only, transit-friendly, or (for northern climes) only-in-summer. It should be so easy I don’t bother with the verbal barrage. You’re going to Mexico City? Let me send you a link.

Libraries on Tumblr, archives on Instagram, newspaper morgues on Twitter are all examples of taking historic material to where people are already spending time, interleaving their daily updates with flashes from the past. Mapping design history in real time could have the same effect for cities, overlaying history—with a personal voice, and good visuals—on streets more often dominated, in-app and in real life, with commercial considerations. You can’t always look at the world through the lens of architecture criticism, but it can make for a nice vacation.

On X

Follow @LangeAlexandraOn Instagram

Featured articles

CityLab

New York Times

New Angle: Voice

Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness