A Sustainable Brownstone Transformation In Brooklyn

The street facade of New York City’s first certified Passive House, known as Tighthouse, is clad in pale gray stucco, sculpted with a few historic-looking details. But, if you knock on that wall, it sounds hollow: The stucco is merely the outermost layer in a 20-inch-thick insulated sandwich. The original brick is buried deep inside, where it can do no harm—via chinks, cracks, or settling—to the supersealed box this 19th-century, 3,120-square-foot Park Slope house has now become. The cornice, too, is a lightweight contemporary replacement: a hollow fiberglass shell mimicking a wood original.

The smooth, low-maintenance surfaces are a far cry from the derelict three-story row house designer Julie Torres Moskovitz first saw in 2009. The brownstone’s front facade was pocked and cracked, the back wall was falling apart, and the interior left a warren of mystery rooms (including one lined with a one-way mirror). The owners, a young couple just starting a family, weren’t daunted by the damage because they wanted a clean, modern renovation to showcase their art collection. “The owners say they don’t like anything organic,” says Torres Moskovitz. “Only concrete and steel.

The original idea was a net-zero house. “That concept starts with using less rather than producing more,” says one of the owners. “We wanted to put less stress on the communal infrastructure.” He began researching Passive Houses, visiting an early iteration in Philadelphia and collecting consultants’ names, including Torres Moskovitz of the environmentally focused Brooklyn design practice Fabrica718. At his encouragement, Torres Moskovitz completed Passive House trainings in New York and Dublin; she is now a certified Passive House tradesman.

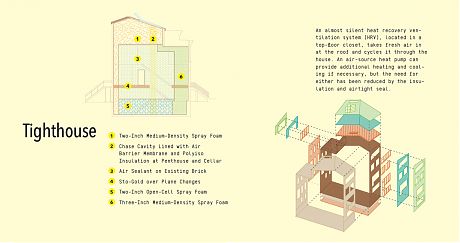

Passive House certification is performance-based, focused not on any renewable or recycled materials used but on how efficiently the building breathes, heats, and cools. That meant that much more than the original facade had to go. Torres Moskovitz specified triple-glazed, argon-gas Schüco windows and doors for the front and back. On the parlor floor, the windows have the same tall, lean proportions as those of traditional brownstones, but they are mullion-free and have a special coating that helps warm the house in the winter. Within the white walls, mounted on studs and insulated with medium-density foam, the windows have been individually sealed with an Intello Plus membrane and Tescon Profil tape. “It’s akin to gift-wrapping,” says Torres Moskovitz. “The materials cost about $3,500, and it took two weeks to seal every window.” The owner and the architectural designer had to seal a window themselves to convince their contractor, generally an ally, that it was worth the extra elbow grease.

Torres Moskovitz describes her clients as “members of the iPhone generation. They think everything should be as intuitive, as simple, and as low-maintenance.” Given the high standards for the Passive House envelope, they wanted to spend their budget on the exterior and were willing to economize on finishes inside. “The house was built in 1899, and in those 100-odd years no one had ever substantially renovated the infrastructure,” says the owner. “This was our big chance to make changes.” To make those interior economies look good, the home’s materials palette was left minimal, assuming the clients’ art would provide color later. “Julie did a fantastic job with the architecture,” says one owner. “Those beautiful moments don’t need accentuating.”

One such moment is the decision to open up the back of the house with larger, north-facing windows in the open kitchen. This might seem like a no-no—more glass has the potential for more heat loss—but the Passive House Planning Package, a proprietary energy-modeling software, makes it easy to weigh trade-offs. Even more light is filtered into the dark center of the row house via a three-story light well, which creates catwalk-like hallways on the second and third floors.

All that remains of the original interiors is a multistory brick wall that stretches up three floors from the center of the parlor. But even this is less authentic than it appears: The owner wanted a respite from the white and gray and requested an exposed brick wall. But brick parti walls are often leaky, due to old mortar and irregular repairs. So the contractor made the real parti wall airtight with a paint-on sealant and then built a new brick wall in front, reusing brick from the two disassembled chimneys. Why no fireplace? Think about it, Torres Moskovitz says: “It’s essentially a hole through your house.”

On X

Follow @LangeAlexandraOn Instagram

Featured articles

CityLab

New York Times

New Angle: Voice

Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness