Why Wooden Toys?

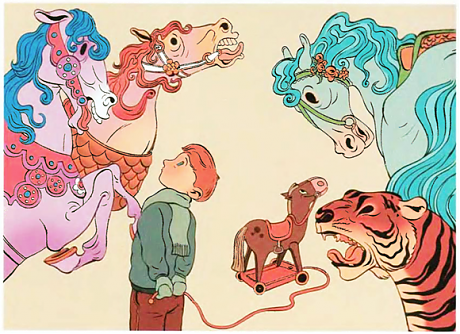

Illustration by Zohar Lazar

“Love LEGO but hate plastic?” asked Apartment Therapy in March, just one of more than a dozen design blogs to feature wooden Lego blocks, made by Mokulock, this spring. Described as “handmade” and “all-natural,” the eight-stud-size blocks have clear visual appeal, in the minimalist Muji way, and come packaged in a brown cardboard box, with an unbleached cotton sack for storage. One commenter dreamed of brick and concrete varieties, as well, to teach children about real building materials.

But beyond the blocks’ good looks lurked some very basic questions of function. Design Boom noted a product disclaimer that “the pieces can warp or fit together imprecisely due to the nature of the material in different temperatures and scale of humidity.” Another commenter brought up sustainability, “considering the sheer number of Lego blocks produced a year.” Are Legos even Legos without the universal snap-together property? Do toys need to be as artisanal as our food? I understand why my child would want to make his own toy, but does someone else need to do it for him? And why wood?

In her new book, “Designing the Creative Child: Playthings and Places in Midcentury America,” Amy F. Ogata explores the answers to these questions by taking us back to the past. Back to the postwar period, specifically, when parents began to pour time and money into products and spaces that would make their children more creative. The baby boom restructured the American landscape, creating a demand for thousands of new schools, new homes, and expanded institutions. With this new construction came new thinking about how, where, and with what tools American children should be educated. Creativity, closely aligned with individuality, was seen as a character trait necessary for the democratic citizen, Ogata writes—a contrast to an image of the more rigid, state-directed child rearing in Soviet countries. The result was a miniaturized version of the postwar “consumer’s republic,” with products created to answer “needs” in thousands of new categories.

It’s shocking, as Ogata tours you through the playrooms, schoolrooms, and science museums of the era, how much of the current aesthetic landscape of upper-income childhood—delights and anxieties alike—was constructed in the late nineteen-forties and nineteen-fifties. The only major change is that now we like our adults creative, and our children smart.

On the question of wood, Ogata writes, “Among the educated middle and upper-middle classes, wood became the material symbol of timelessness, authenticity and refinement in the modern educational toy.” She quotes Roland Barthes, who characterized plastic and metal as “graceless” and “chemical,” and argued that wood “is a familiar and poetic substance, which does not sever the child from close contact with the tree, the table, the floor. Wood does not wound or break down; it does not shatter, it wears out, it can last a long time.” Dr. Spock argued for the abstracted wooden train over the realistic metal one, while Creative Playthings, an early educational toy store and catalogue, combined furniture and toy in the Hollow Block: maple cubes, open on one side, that could be used for storage or fort-making.

If you look at high-end children’s furniture today, it still subscribes to this bleached aesthetic: the Oeuf beds, which notch wood and white panels; the Offi chalkboard table, which combines Eames-inspired bentwood legs with a surface ready for creative activity. To what do we owe the success of Melissa & Doug toys—made cheaply and not to last, often with a single playable quality—but their base layer of wood? Mokulock uses language very close to that of Barthes in its promotional material: “Mokulock’s intention is to provide children who grow up in an urban and rather sterile environment with the possibility to connect to and understand nature and ecology in a playful manner.”

Building toys, of whatever material, were a popular category in postwar designs aimed at children: the Walker Art Center developed the Magnet Master, steel plates in basic shapes; Charles and Ray Eames created the patterned-cardboard House of Cards; Colorforms let children build, play, and learn with rubbery colored shapes. Those simple shapes and primary colors were repeated, at larger scale, in playgrounds and playrooms. Ogata describes the winning designs from the 1953 Play Sculpture competition (judged by, among others, the architect Philip Johnson) like a series of blown-up blocks: a “playhouse with pierced panels and a trellis of metal rods,” “spool-shaped upright forms,” and bridges that offered “places to crawl or hide beneath.”

An important aspect of these and other mid-century playgrounds was the use of elements that children could manipulate themselves. Richard Dattner and M. Paul Friedberg, the designers of several Central Park playgrounds, paraphrased the Swiss developmental psychologist Jean Piaget, who held that the “ability to transform some aspect of the environment … gave the child a sense of control and mastery.” The blue foam Imagination Playground blocks, now on exhibit at the National Building Museum, in Washington, D.C., as part of a show called “Play Work Build,” are but an updated version of those early trellises, spools, and bridges, intended for the same manipulations.

If our playgrounds have slipped backward into representations of forts and cars, with fixed pieces and soft landings, our playrooms have only increased in size and splendor. Ogata quotes Margaret Mead, reading postwar American childhood through the creation of new categories of age-specific consumer products: “Americans show their consciousness that each age has its distinctive character by all the things that are fitted to the child’s size, not only the crib and the cradle gym and the bathinette, but the small chair and table, too, and the special bowl and cup and spoon which together make a child-sized world out of a corner of the room.” Ogata traces the way children’s areas grew from corners to stand-alone spaces in the new open-plan postwar houses—not unrelated to manufacturers’ desire to sell more toys, and more furniture to store them. (What is Land of Nod but a purveyor of more attractive receptacles for toys?)

Ogata summarizes the cultural historian Lisa Jacobson’s argument, in “Raising Consumers,” that “educators and parents believed that wholesome educational occupations and amusements redirected the child from the position of a mere spectator—one of the fears that accompanied the rise of popular cinema—to that of an active creator of his or her own world.” One such example is finger painting, which Crayola manufacturer Binney & Smith popularized as (and sold supplies for) an activity that “helps children develop their senses … feeling, seeing, moving.”

In this anxiety, too, we are at one with our grandparents: buying the toys that keep our children in close contact with the tree, even as we surrender to the iPad. The handmade and all-natural aesthetics of mid-century toys have also infected the world of digital toys, where one can choose between games made by Disney, with endless pop-ups and merchandising tie-ins, or games like Hopscotch, with sans-serif fonts, colored bars, and the message “Empower them to create anything they can imagine.” For kids, coding is the brand-new playroom, a way to become creators rather than consumers—after we buy them just one more thing.

On X

Follow @LangeAlexandraOn Instagram

Featured articles

CityLab

New York Times

New Angle: Voice

Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness