Color Games

Can the pink-and-blue divide in toy design ever fade away?

Many pairs of eyes stare out from the toy shelves at Morning Glory, a stationary store in Flushing, Queens. Big eyes. Small eyes. Eyes that can be made to blink. Eyes with lashes, and eyes that are a perfect circle. But as you scan, with your own, human, blinking, squinting eyes, from one end of the aisle to the other, you notice something: All the eyes are on one end—the pink end. On the other—the blue end—the eyes are replaced by a different round thing: wheels.

On the pink side, Chelsea Can Be, a doll from Mattel’s line for kids too young for Barbie, plays out a narrative of female empowerment with accessories for teaching, sewing, pet care, and construction. On the blue side, Hot Wheels offers a Fat Ride, or the chance to “dodge the attacking Piranha Plant” with Mario and friends.

“They literally made a diagram for my A.I. Toys,” says artist Ani Liu, filming the scene with her iPhone. “It goes from really pastel light pink to black and red and blue. From nurturing to aggressive behavior.”

Liu and I are here in Flushing to observe in person the digital phenomenon she critiques in her ongoing series, A.I. Toys, currently on view at Northeastern University’s Gallery 360 in Boston. For that series, Liu, who has degrees from the Harvard Graduate School of Design and the MIT Media Lab, feeds a machine learning model real data about the toys sold online at Amazon and Target and generates new playthings based on the labels, descriptions, and colors the model spits out. Unsurprisingly, the results are highly gendered.

“Girls’ toys are mostly about makeup and domestic things like kitchens. Soft things, glittery things. Boys’ toys are simulations of war,” Liu says, who, sporting a sharp black bob and a Patagonia kneelength fleece jacket, is eliciting a sense of both hard and soft. She began looking at toy ads from the 1920s and found the same split as we observe in the store: Girls were sold a miniature broom and carpet sweeper with the tagline, “Every little girl likes to play house,” while boys were pitched Erector sets and told, “Every boy likes to tinker around and build things.”

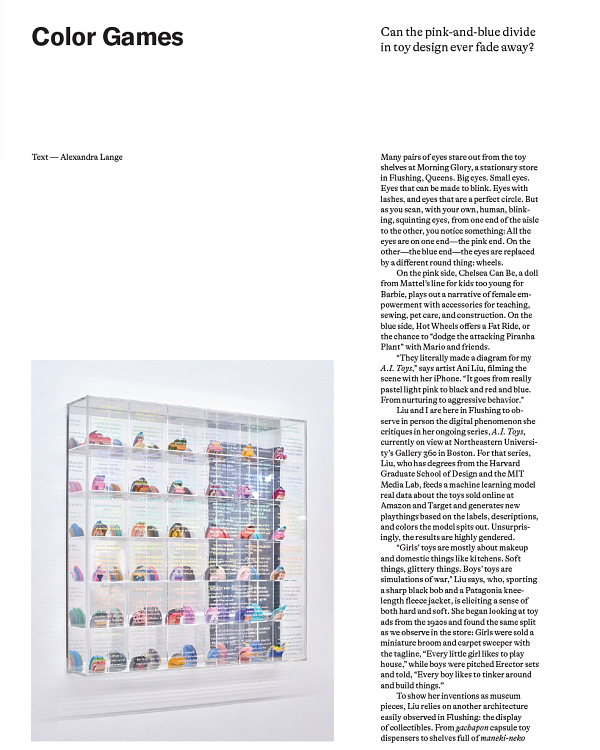

To show her inventions as museum pieces, Liu relies on another architecture easily observed in Flushing: the display of collectibles. From gachapon capsule toy dispensers to shelves full of maneki-neko lucky cats (which Liu’s partner collects), grids of adorable objects pop up across the commercial landscape. Liu takes the digital toy images and pixel-sorts them into gradations of color and shape, which are then 3D printed at bonbon-size.

The boys’ toys come in an ombre of army greens and browns, the girls’ toys in aquas, pinks, and lavenders. In A.I. Toys, these then sit on shelves in front of wall-mounted screens writing their descriptions in real time. It’s like every overtired parent’s late-night search for a birthday gift put in a blender of stereotypes and shades. One example: Silver Scented Pony Hair Barbie Doll. “Behind closed doors, this kid-friendly spa playset turns children’s natural hair into a luxury,” Liu explains. The associated object is pinky-purple and shaped like a castle.

Liu is far from the first artist to document this phenomenon, though few others have done so with such technological grace. Korean photographer JeongMee Yoon’s The Pink and Blue Project famously captures portraits of children in their bedrooms centered in seas of pink or blue toys; she later revisits them as tweens and teens documenting how the quantity of toys, and the gendered color separation, diminish over time.

Historian Amy Ogata, author of Designing the Creative Child: Playthings and Places in Midcentury America, dates the pink-and-blue-ification of the toy market to the postwar era, when rising prosperity made it possible for parents to buy entirely separate wardrobes and toy chests for their kids. While some early-20th-century toys were specifically marketed by gender (dolls for girls, tool sets for boys), many more were presented as neutral, including blocks, balls, pull-toys, and animal figurines.

Despite a brief unisex interregnum in the 1970s, the pink and blue standards remain, boosted since the 1980s by rising conservatism and medical advances that have allowed more parents to know the gender of their child before birth. Manufacturers again saw an opportunity to sell parents two sets of baby clothes and two sets of toys.

The diversification and separation of toy lines has only increased over time. When LEGO was first introduced in the U.S. in the early 1960s, ads showed both boys and girls playing with this “quiet toy.” But by 1971, LEGO introduced the Homemaker series, which included dollhouse-like sets with furniture for every room of the house, as well as a hair salon, school, and hospital. The colors were cheerful primaries, but only the hospital box shows a boy at play.

The flipside of the digital dominance of pink and blue is That Sad Beige Lady (sadbeige on TikTok, officialsadbeige on Instagram), which skewers the pretensions of designers and parents who insist that everything in their homes be natural and neutral. Yes, dressing your child in dun-colored sacks and avoiding anything battery operated provides an out from the gendered online world, but why do all the elements of beige life have to be so expensive? That seems to be the question of Sad Beige alter ego Hayley DeRoche, asked in a Werner Herzog-inspired German accent. Why do the children look so sad? Who really wants stacking cups in colors that range from oatmeal to mulberry?

The answer, unsurprisingly, is parents, performing the old dance of class-based inconspicuous consumption by paying more for less. Ogata’s book has an explanation for this, too: Wooden toys, popularized in the early 20th century by a series of progressive educators, were always more costly than tin, paper, and plastic, and developed a reputation as fostering creativity. By purchasing the unlabeled, unbranded, and unpinked, parents are demonstrating their dedication to going against the grain—albeit in an entirely conformist manner.

Liu, who has a daughter and a younger son, is now wrestling with the issue of what is neutral. Does it feel different to let your son dabble in pink than letting your daughter choose blue?

While the toy aisle’s gender demarcation remains very much intact, Liu believes the free experimentation in fashion might help finally erode the pink-blue divide. Gen Zers, in particular, are happily bending rules. She sees this phenomenon also visible in Yoon’s portraits of adolescents. “There are more style icons like Harry Styles who are more fluid. Crop tops will appear on boys and on girls,” Liu says. “I have plenty of male students who paint their nails and wear platform shoes.”

On X

Follow @LangeAlexandraOn Instagram

Featured articles

CityLab

New York Times

New Angle: Voice

Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness