Inside Richard Neutra’s 1949 Wirin House

Photograph by Chris Mottalini

Home improvement books often start with a caveat: “Don’t make big changes until you’ve lived in the house.” When the home is a midcentury gem by the legendary modernist Richard Neutra, that advice comes with teeth. “We have to be very careful,” says Alberto Chehebar of his residence, the 1949 Wirin House in Los Feliz, California.

His wife Jocelyne Katz puts it more bluntly: “The house owns us.” This sense of stewardship has been deepened by the recent fires in Los Angeles; many of the city’s other houses, threatened or lost, were built on similar hillside sites.

Sorry, Kids: Disney’s New York Headquarters Is for Grown-Ups

The new 1.2 million-square-foot office building features two towers with multiple terraces. Dave Burk/SOM

On the outside, there are no mouse ears. No dwarf caryatids. No Sorcerer’s Apprentice hat. The new headquarters of the Walt Disney Company at 7 Hudson Square, the Robert A. Iger Building, does not partake of the architectural whimsy of the Magic Kingdom — and nor should it. No one is dreaming up cartoon characters within.

Instead, the all-electric, solar-powered, high-performance building brings together Disney’s news, editorial, streaming and live production divisions under one roof, along with back-of-house departments including advertising, technology and corporate, making the company’s public face more akin to midtown media conglomerates than Burbank creative studios. The building is a stage, not the main character — from the swoop of blonde bentwood in the western lobby, which suggests a pulled-back curtain, to the terraces that give employees and visitors views of the surrounding buildings and, beyond their cornices, the Hudson River.

“Bob Iger was always saying, this is a place people come to be creative, not to balance ledgers,” says Colin Koop, design partner at SOM. The team went through hundreds of different greens before they brought six terra cotta panels to a Manhattan rooftop for Iger’s approval. “We wanted to imply this was a creative company on the façade, confidently but subtly.”

How to Build a Neurodiverse City

Students play in soundscape pods designed by Interboro Partners.

The sounds of highway car traffic grate on most people trying to focus. But that’s particularly true for some of the students of PS112m in New York City.

“This is a school that serves students with special needs, and many of them have sensory sensitivities,” says Georgeen Theodore, founder of multidisciplinary design firm Interboro Partners. “Their playground is directly adjacent to the FDR [Drive], which is a major source of noise,” as a multi-lane highway that hugs the East River along Manhattan’s edge.

The school hosts one of NYC Public Schools’ Nest Programs, in partnership with New York University, to serve students with autism spectrum disorders in classrooms alongside general education students.

Cities and schools are not typically designed by, or for, people with conditions such as autism. Often, the processes for how they get built exclude input from neurodivergent residents, a category that can include people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, dyspraxia, dyslexia and intellectual disabilities as well as mental health conditions like anxiety, depression, and PTSD.

Architects are developing ways to address these oversights — first experimenting with new ways of surveying diverse users, then designing with the insights they receive.

New York’s First ‘Passive House’ School Is a Model of Downtown Density

Pavel Bendov/James Ewing/Sarah Schumacher for Bloomberg

Building a school in a city is always a bit of a puzzle. Without the sprawling exurban lots that so many school districts favor, there’s a balancing act between recreation space and classroom needs, efficient movement of kids and places for them to stretch out, welcoming entrances and secure facilities. But those were only the first set of challenges Architecture Research Office (ARO) faced in designing a 146,000-square-foot public primary school and high school on one of Brooklyn’s busiest thoroughfares: The twin facilities were also part of a full-block development atop a 100-year-old subway tunnel, and they needed to achieve the rigorous Passive House efficiency standards.

“Honestly, one of the things we are good at is that puzzle of, ‘How do you come up with a rational and good architecture, no matter what the constraints are?’” says ARO principal Stephen Cassell. “We will rarely say no.”

The new Elizabeth Jennings School for Bold Explorers (aka PS456) and Khalil Gibran International Academy (KGIA), an existing Arabic language high school, opened in September in a pair of interlocking structures, designed for permanence and calm despite numerous overlapping agendas. The approximately $150 million construction cost came from New York’s Education Construction Fund, which supports private development projects when combined with public schools.

The Year of Meh: It’s the 2024 Architecture and Design Awards

By Alexandra Lange, Mark Lamster and Carolina Miranda

Better late than never? By now you’ve scrolled through a dozen annual awards with tasteful, oh-so-thoughtful selections. Another fancy house? Boooring. Another chic boutique. Snooze. Another monochromatic gridded curtain wall. Yadda yadda yadda. Not us! We know what you really want, and for the fifteenth consecutive year (in starchitect time, that’s four monographs, three marriages, and two me-too scandals) we bring you our own no-holds-barred scorecard of all that made us happy and sad in 2024. You might think, in a year in which two of the biggest Oscar-bait films were about architects (listen to our podcast about them here or here!), that the IRL architecture itself would be scene-stealing, dramatic, magnetic and yet — not so much.

This year, for the first time, we are also providing audio commentary! A companion podcast by Architecture Writers Anonymous (a.k.a. our groupchat) can be found at Spotify and Apple

Burned Out Parents Need Better Public Spaces

A Philadelphia Playstreet. Photo by Ken McFarlane/Philadelphia Parks & Recreation.

Family life has always been stressful. But a recent declaration by the US Surgeon General that parenting is a public health crisis has reignited conversations about how families might stop the endless spiral of expectation. What’s been less discussed is how the physical design of housing, transportation and public space makes life harder by increasing commute times, reducing communal play spaces and creating barriers to children’s mobility.

Parenting experts say children need to learn independence and resilience. But cities and suburbs don’t offer safe pedestrian and bike routes to school, malls kick teenagers out on the weekends, and free time disappears under a spreadsheet of activities. All of those “musts” take more of the parents’ time or money to navigate, because the child can’t do it on their own.

As Darby Saxbe, a clinical psychologist, recently wrote in the New York Times, “underparenting requires structural change.” Unlike most political pundits, she’s not just talking about economic policies like family leave and subsidized child care. She’s talking about actual physical structures, and the cultural change required to populate them. We need to “build back our tolerance for children in public spaces,” she writes, “and create safe environments where lightly supervised kids can roam freely.”

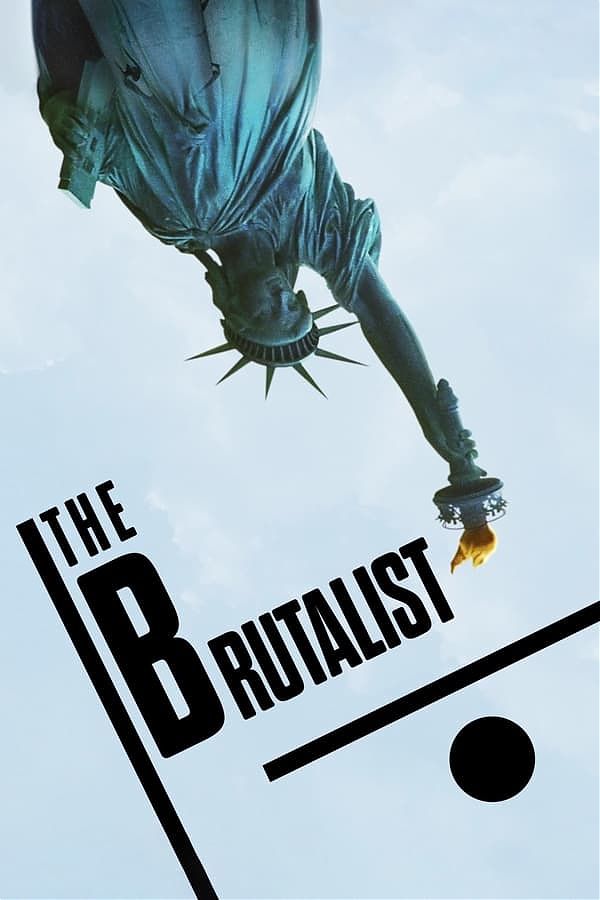

Why 'The Brutalist' Is a Terrible Movie

Architecture and culture writers Mark Lamster, Alexandra Lange and Carolina A. Miranda get together to put a spike into Brady Corbet’s architectural magnum opus, “The Brutalist.” Spoiler alert: this is one big spoiler.

You Turned a Mall Into Housing?

Interview with Anjulie Rao about the feasibility of turning malls into housing.

As strange as a recent viral project in Milwaukee may seem, there’s a historical precedent for this kind of adaptive reuse—but that doesn’t mean it’s always done right.

If you’re of the Gen X or millennial generations, chances are, much of your youth was spent at the mall: buying Beanie Babies at Scoops!, eating at the food court, or accompanying your parents to Sears. For nearly 70 years, shopping malls were an important part of community life in many cities and suburbs—yet, of around 2,500 malls that existed in 1980, only 700 remained as of 2023, according to commercial real estate analytics company CoStar. For many Americans, this means central places of gathering and commerce have declined to the point where their abandoned interiors have made for excellent ruin porn.

But these massive structures are also seeing a rebirth as a much-needed entity: housing.

The Rainbow Connection

Hoover Elementary School in Oakland, CA. Photo by Marissa Leshnov

The minds of children are particularly receptive to color; the rainbow is one of the first vocabularies that they learn, and the hues allow them to absorb concepts easily—without losing emotional power. Laura Guido-Clark’s understanding of that power solidified when she saw The Wizard of Oz at the age of 10. “I realized that Oz was supercharged; it was full of hope and joy and wonder…” she trails off. “Films have such a short time to tell a story, and the fact that color was connected to story was a big part of their appeal for me.”

Connecting color to story became her mission, first as a textile designer, and subsequently as a color consultant and developer of the Love Good Color system, a methodology developed to help companies identify what they want out of their products’ palette. One of Guido-Clark’s major successes is Herman Miller’s Cosm Chair, for which she designed and curated three unusual, yet universally appealing hues. Typically, people browse the eclectic colors for big furniture purchases, and then pick standard navy blue, beige, and burgundy for their final selections, but with the Cosm, “People were ordering colors like they were ordering neutrals,” she says.

The Answer To Making Cities More Family-Friendly? Courtyards

An interior courtyard at Sunnyside Garden Apartments. Photo Jeenah Moon/Bloomberg.

The population of children under five is shrinking across the US. That group has decreased most rapidly in big cities: 14% in Los Angeles County, 18% percent in New York City and 15% percent in Cook County, Illinois, which includes Chicago.

This is bad news for the diversity and stability of cities, which are improved by the amenities that families seek — parks, public libraries, safe streets. It’s also discouraging for families who prefer to live in the city or don’t have the option or desire to move to the car-dominated suburbs. Any effort to retain families has to start with housing, their primary expense.

That one weird trick for making cities more family-friendly? We’ve known it for decades: It’s the courtyard.

On X

Follow @LangeAlexandraOn Instagram

Featured articles

CityLab

New York Times

New Angle: Voice

Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness