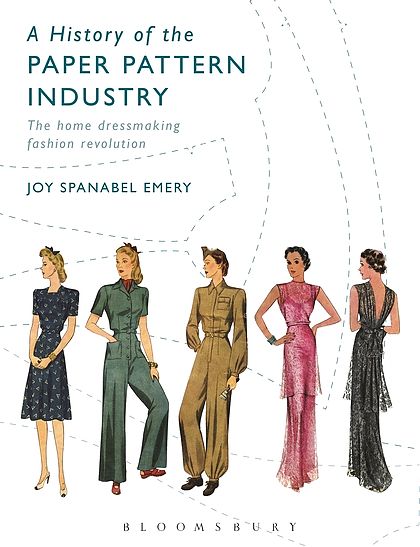

Review: A History of the Paper Pattern Industry

The Commercial Pattern Archive, located at the University of Rhode Island, is a wondrous thing, a visual chronicle not only of the vicissitudes of sewing over the past century and a half, but also a window into home technology, fashion, and the rights and roles of women. A History of the Paper Pattern Industry by Joy Spanabel Emery, the archives’ curator, wends its way through that chronicle’s highlights, offering illustrative examples of the way patterns reflect media, love and war. It’s an academic book, alternately dry and fascinating, so I offer highlights by way of review. I hope others, inspired by this beginning, will take it and run in different interpretive directions, as I did with the 3D printer. Apologies for the home-sewn photography.

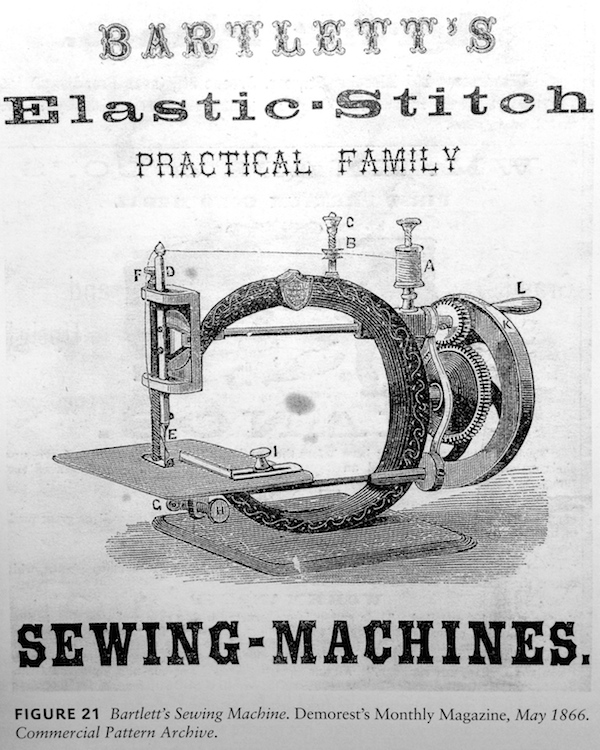

The first home sewing machine was designed in 1856, and cost $125 ($2,997 in 2010 or, about the cost of a 3D printer today). To offset the cost for individuals, Godey’s Lady’s Book suggested that families pool their resources and buy one together (like Techshop for the rural village); others offered rent-to-own plans, $5 down and the rest to be paid with interest.

Women took to the new machines faster than their male, professional colleagues. This caused concern not only that home sewing might put tailors out of business, but also that it might make women’s lives too easy. Betty Williams noted, “many men wanted to believe that women couldn’t handle such a complicated piece of machinery; they feared that if women did perform their sewing duties in less time there would be time left over for them to improve themselves or participate in the suffrage movement.”

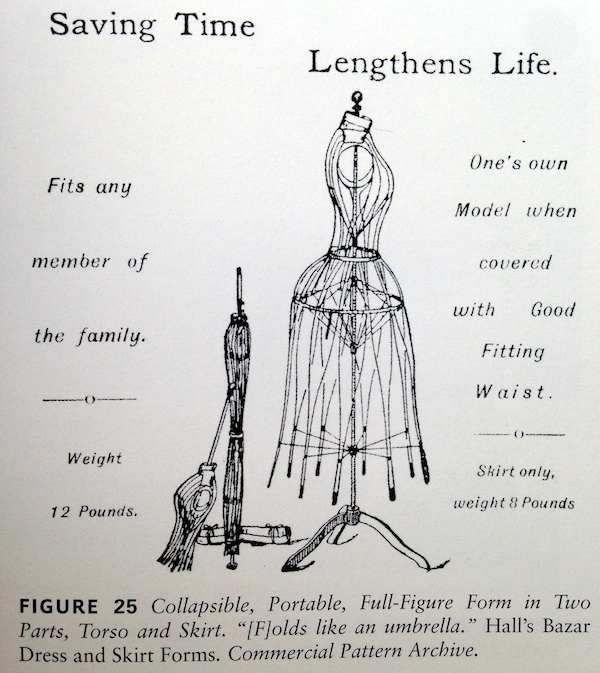

Sewing machines were not the only technology that needed improvement: the dress form was also the subject of design innovation and experiment. Hall’s Bazar Form Company adapted the idea of the umbrella, with metal ribs that can be collapsed or expanded, into a two-part form (torso and skirt) that could be collapsed into a column for storage.

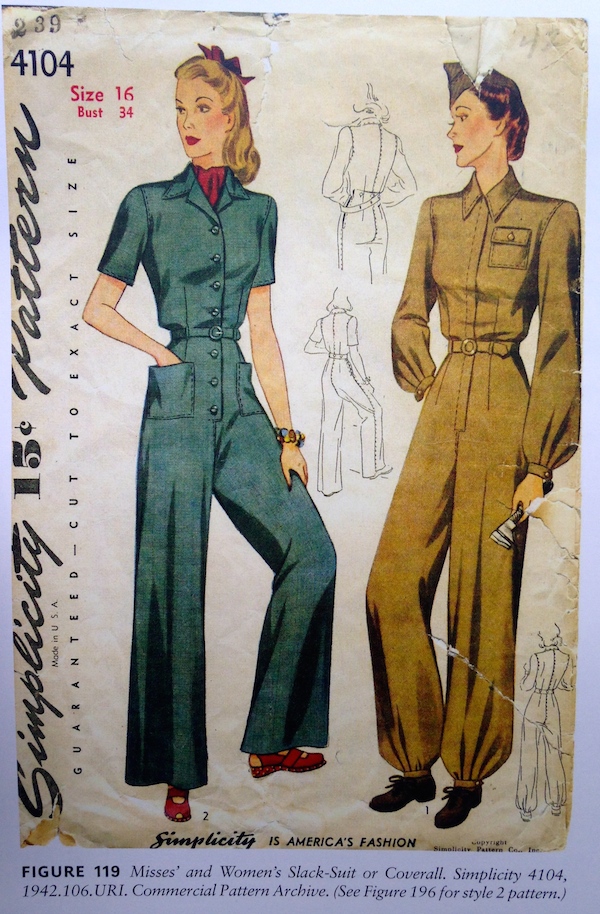

The first World War affected the pattern industry in a number of ways. “The Dress of Patriotism,” published by McCall in 1918, was advertised as requiring only two yards of 54-inch material, saving wool for “over there.” McCall also published a pattern for a ladies’ work suit, as recommended for women in the cavalry corps or defense plants. Other companies created patterns for Red Cross nurse uniforms, as well as operating masks, gowns and hospital robes to be sewn and donated to hospitals.

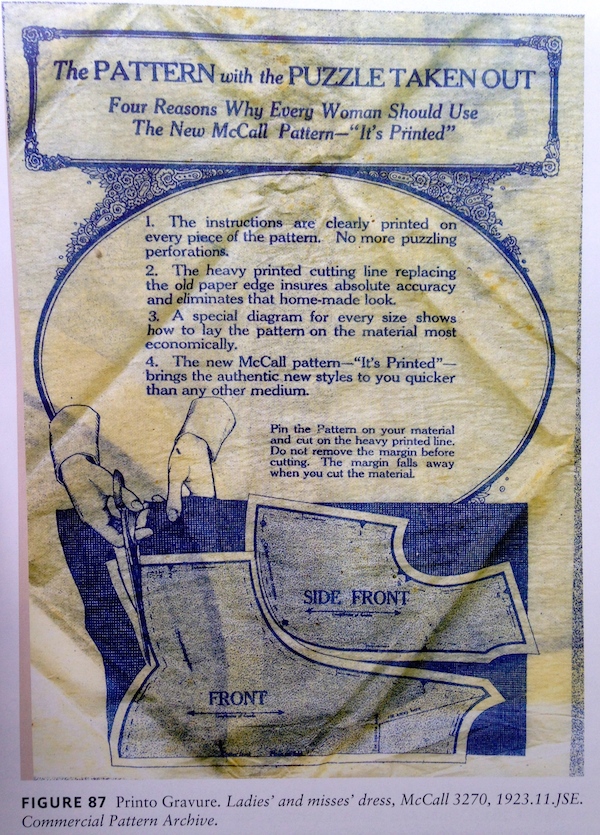

Before 1920, commercial patterns had been machine cut and punched, and home sewers had to learn a common language of punched holes corresponding to different cuts, pleats, and other moves. The McCall Printed Pattern was announced in 1921 as “the biggest invention since the sewing machine.” Pattern pieces were printed in outline, along with all other markings indicating darts, alignment, and the name of each section. The McCall tagline, “It’s printed,” recalls Lucky Strike’s, “It’s toasted,” as a minimalist indicator of a serious difference. McCall rivals came up with ways around their patent; Pictorial Review wrote that the new pattern markings were so clear it “ALMOST TALKS TO YOU and answers all your questions satisfactorily and promptly.”

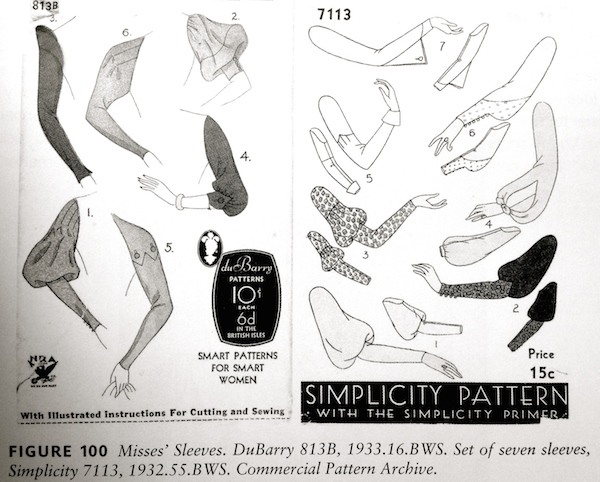

During the Depression, women tried to reuse patterns and recycle clothing, leading to an alternative market for refresher pieces like sleeves, collars and cuffs. I love the abstraction of these covers from DuBarry, which suggest the limited range of our current sleeve choices.

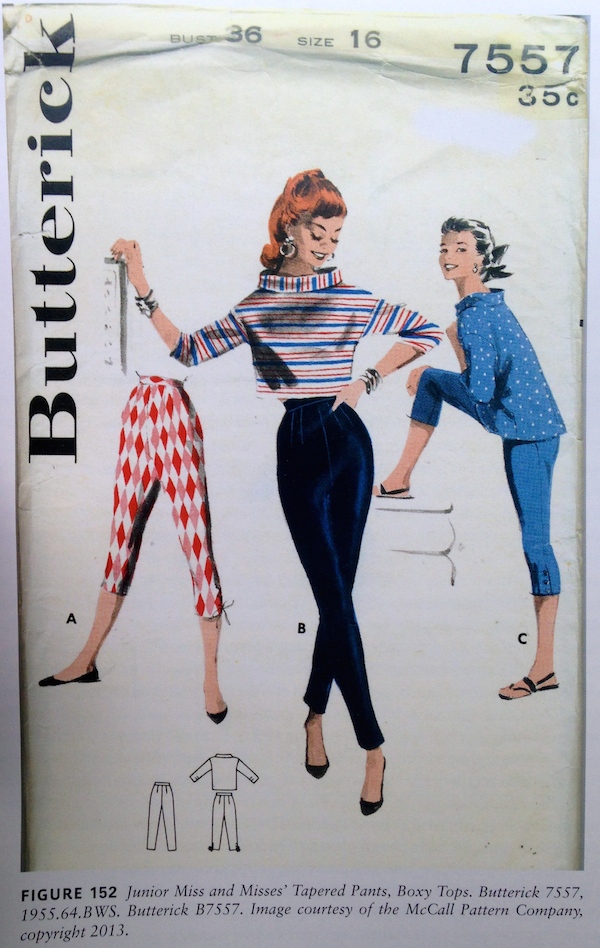

Emery writes, “a common misconception is that by the 1960s women stopped sewing and making their own clothes due to the mass of inexpensive, readily available ready-to-wear options. However, the 1960s were actually a boom period.” Celebrity endorsements, TV advertising and educational programming, plus manufacturer-sponsored sewing classes in schools all contributed to a 40M individual market, averaging 27 garments per person per year. Four out of five teenage girls made their own clothes. “The summer 1967 issue of American Fabrics stressed the growing appeal of sewing to express individuality and as a mark of elegant economy.”

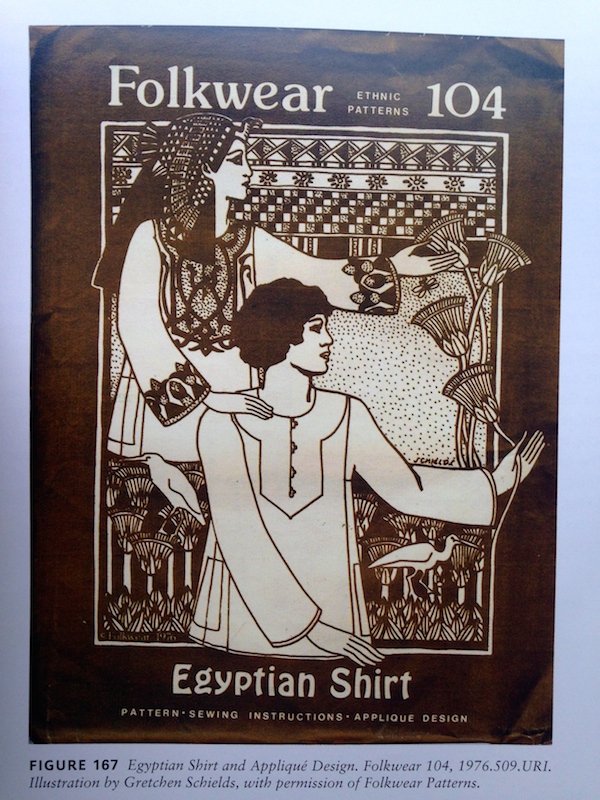

Trends of the past, as interpreted through paper patterns. The minidress.

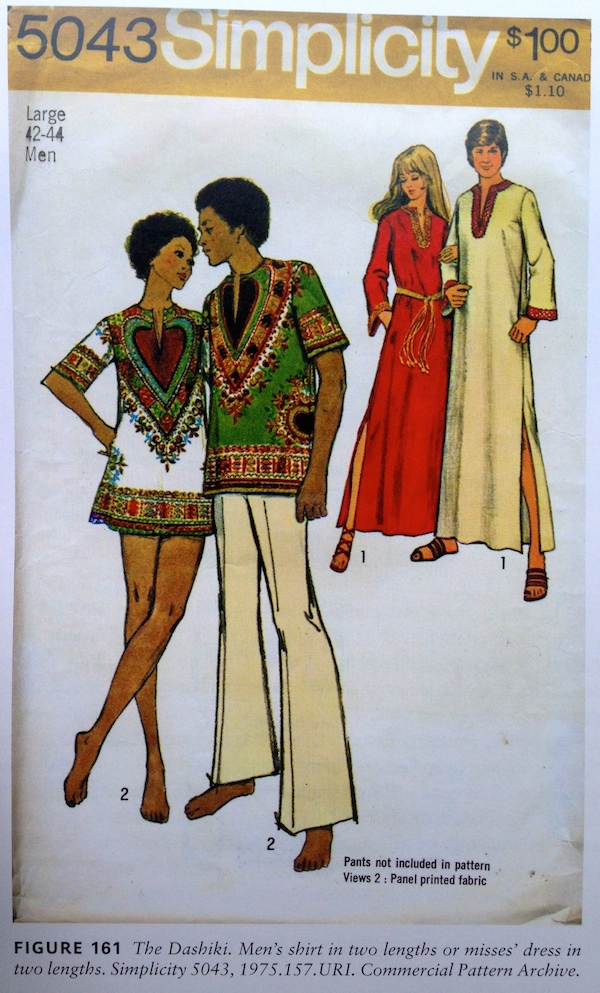

The dashiki.

Dynasty.

By the 1980s, home sewing was shrinking. And yet the history ends on a hopeful note, with a smaller, more focused revival of interest spurred by the combination of digital technology and the sewing machine, through automation, apps, and embroidery at the push of a button. Pattern design focused on parts of the market not served by ready-made clothing, like traditional clothing, historic recreations, and children’s gear. The appendix to Emery’s book offers reconstructed patterns first issued from 1850 to 1960, should you want a pointed basque, a drop-waist 1929 sheath, or a Nehru jacket. Project Runway didn’t hurt either. Digital forums provide the modern-day equivalent of the sewing circle, offering ideas, encouragement and trouble-shooting even when one is sewing alone.

Review: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph

There’s one in every group. A nonbeliever, that is. Most of the people who have shown up on a recent Saturday afternoon for a tour of Paul Rudolph’s Government Service Center (1971) are already convinced there is something to see here. We take photos of the signature “corduroy” concrete at the entrance, as well as the patinated plaque with Rudolph’s name. We look sadly at the chain-link fences walling off Rudolph’s signature banquette seating (not to code). We listen as Timothy M. Rohan, author of the first complete monograph of Rudolph’s work, talks about the theatrical, even therapeutic, components of his Mental Health Building. The sinuous stair that spills, in concrete waves, down onto Staniford Street more than underlines the first point; we have to take Rohan’s word for the second, as the interior, still in use, is off limits. A middle-aged man in a plaid shirt is having none of it. He sputters, he shifts, his body language and his increasingly aggressive mutterings point to just one question: “You like this stuff?”

Airbnb Logo Redesign

I can’t get worked up about these baby logos. LMN when they’re adding highlights to another Paul Rand.

— Alexandra Lange (@LangeAlexandra) July 16, 2014Portfolio | Lisboa 7

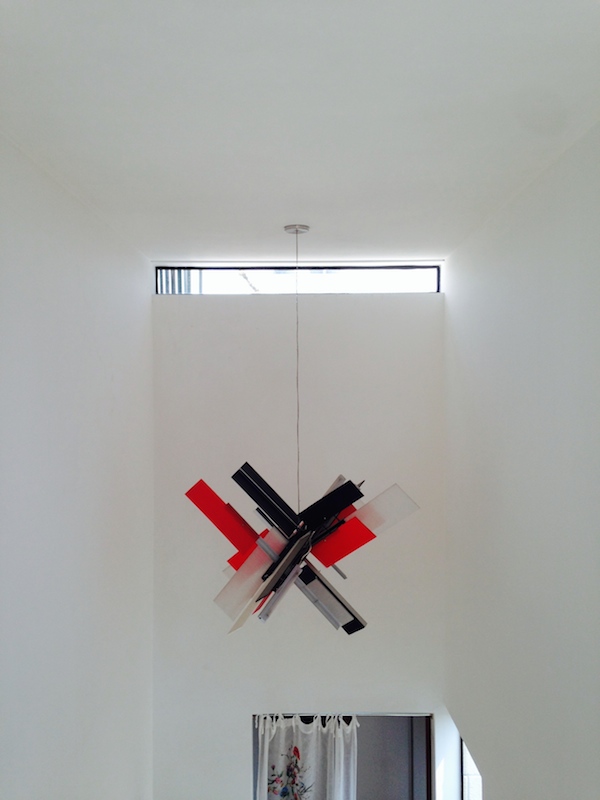

The latest issue of Uncube Magazine, No. 23, is devoted to Mexico City. Mimi Zeiger contributes an article on emerging practices that includes the work of AT103, designers of the fascinating housing project Lisboa 7. As she writes,

In the 2013 book Architecture Does (Not) Matter, AT103 chronicle their housing project Lisboa 7 through photographs, analytical drawings, and essays. It is an ode to the concrete block, and an investigation into how reducing architecture to fundamentals allowed the firm to radically reinterpret housing. Their scheme breaks down the massing into six narrow buildings, each honeycombed with courtyards and windows for maximum light and ventilation. “Form follows strategy”, Pardo quips. The blocks were left bare to reduce the cost of the enlarged exterior envelope.

I had the pleasure of touring Lisboa 7 with Francisco Pardo (above) while I was in Mexico City, and I took these photos. What struck me the most, as a visitor from Brooklyn, was the slicing and dicing of the open space on a narrow lot, reorienting most of the apartments to internal lightwells rather than windows only at the front and back of the lot. I’m all too familiar with the brownstone pattern here, and too few architects have attempted to rethink the 20 by 50 multifamily block. I also appreciated the way AT103 allowed for a much broader range of apartment size, from studio to three-bedroom, by creating modules that could be combined up and down and sideways. This seemed to be a recognition of the informal patterns one sees in older apartment buildings, made modular by necessity. It is also an idea raised by Jeanne Gang’s team in MoMA’s 2012 Foreclosed exhibition, anticipating the range of housing choices we need over time all happening in a single place.

If you’d like to know more, check out Architecture Does (Not) Matter and more photos at ArchDaily.

Review: Radical Cities

“Considering ideal conditions is a waste of time,” Alfredo Brillembourg and Hubert Klumpner write in their 2005 book, Informal City. “The point is to avoid catastrophe.” The two architects, partners in the international practice Urban-Think Tank, are known for the cable car system they designed for Caracas, connecting barrios in the hills with the city in the valley. Part of the allure of these cable cars, and U-TT’s work in general, is the way they make a virtue of leftover spaces. A shelter for a football field becomes a “vertical gymnasium”. A shelter for street children, built under an overpass, gets another football pitch on its roof. As design critic Justin McGuirk writes in Radical Cities, his survey of urban experiments in Latin America, in “engaging with the informal city, U-TT developed a methodology of maximising the amount of social activity that a tiny plot of land could deliver”. They went small – “strategic” and “urban acupuncture” are the terms du jour – looking at what the city had become, and what individual neighbourhoods needed, rather than masterplanning a cycle of demolition and straight lines.

Portfolio | UNAM

The University City campus of the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico (UNAM) was built in Coyocan, in the southern part of Mexico City, in the early 1950s. It opened in 1954 and in 2007 was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site. The buildings on the campus were designed by Mario Pani (whose CUPA housing project I posted last week), along with Juan O’Gorman, Felix Candela, Enrique del Moral, Domingo García Ramos, Armando Franco Rovira, Ernesto Gómez Gallardo; the murals were designed by Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros. It is a stunning site in multiple senses: huge but intricate, repetitive but quirky. We visited on a hot, sunny day in March and had to scurry around the edges of the vast, flat lawn in the middle. The circulation, via shaded paths and smaller courtyards, pushes most people around the edges except for ceremony (or protest). The enormity of the open space offered its own kind of anonymity: in many parks in Mexico City we happened upon couples necking in odd corners. At UNAM, a few were doing so out in the open, apparently feeling the scale as a kind of cover.

The opening date of 1954 is particularly interesting to me. The North American campus to which I think UNAM most closely relates is the General Motors Technical Center by Eero Saarinen, which began to open the same year. There, instead of a flat hot lawn, the empty center is filled with a lake with dancing waterworks. To give it height, Saarinen added a tear drop-shaped water tower; UNAM has the much smaller yellow openwork sculpture shown below. To give it curves Saarinen added a dome; UNAM has vaults and roofs designed in concrete by Candela. Saarinen specified end walls in various brilliantly-enameled bricks; UNAM had the murals, painted, sculpted, tiled, by the country’s best artists, which serve as their own kind of beacons, and add an even more refined level of detail. At GMTC, the only design of the same delicacy is Harry Bertoia’s cafeteria screen. The murals are stunning at a distance, and one is willing to walk great lengths to get closer to them. But when you reach the buildings they are still high over your head, pitched at the masses crisscrossing the campus. You can actually “see” many of them better when they are brought close through photography. The murals by O’Gorman on the library, at the top of this post, for example, are often used to represent all of the University City. On site, they do not dominate.

Other details noticed and appreciated: different textured pavements, curvy benches in a squared-off courtyard, shimmering monochrome tiles, touches of paint, like the bright blue on the architecture school. It is easy to photograph UNAM as a classic alienated modernist scene, and indeed, some of the classroom buildings read as endless. But it isn’t all, or even mostly, like that. And the endlessness relates it to many other complexes of the period, when the Beaux Arts axis was abandoned, and architects northern and southern tried to demonstrate their ambitions for the new era through different combinations of long lines, featured curves, and artistic explosions.

Portfolio | Centro Urbano Presidente Aleman

Visiting two Barragan houses was a dream, but the Harvard Graduate School of Design studio with which I traveled to Mexico this spring was exploring different mechanisms for low-income housing. We looked at a number of examples of mass housing, the earliest being the Centro Urbano Presidente Aleman (known as CUPA, coo-pa), designed by Mario Pani and built in 1949. The complex includes six thirteen-story towers, zig-zags rather than slabs, as well as six three-story rectangular buildings and a variety of recreational buildings and open spaces. For those versed in modern architecture, the Corbusian precedents are obvious: bi-level apartments, outdoor streets in the sky, the combination of low- and high-rise, and the buildings a redent. Here are towers in the park, but in Mexico City the park (thanks to the climate) is lush and green, the flower boxes along those open passages are full, and the idea of a public sitting room thirteen stories up doesn’t seem like such a terrible prospect. The exterior language is inflected toward a Mexican vernacular, the concrete frame roughly textured, with infill panels of brick. In the strip windows overlooking the passages, one could see lace curtains and religious icons. As with so many early modernist developments, in Latin America as well as Europe, the complex’s longtime residents had made it their own.

By all accounts CUPA has been the rare stable example of such mass housing in the region; considered “gargantuan” when it was built to house 5000 people on land designated for 200 single-family houses, it now looks far more reasonable. Stable because residents have stayed by choice, stable because it survived the earthquake of 1985, which destroyed a number of the slabs at Pani’s later, more massive, more troubled Conjunto Urbano Nonoalco Tlatelolco. Justin McGuirk starts his new book, Radical Cities, in Tlatelolco, completed in 1964, and describes it thusly: “Tlatelolco took the modernist idea of social housing to its logical, many would say absurd, conclusion. If, in the mid twentieth century, the city of the future would comprise rows of megablocks sitting in parks and gardens, then the future looked like Tlatelolco.”

It was interesting to see the complex turned into a modern graphic, as at the laundromat on its first floor, as well as to see it remodeled, by one architect-in-residence, into a true representation of International Style decor, with a George Nelson clock and a Marimekko apron. The one complaint we heard on our (admittedly short) visit was that, at certain times of day, you couldn’t take the elevators: the unionized operators did not want to stagger their breaks. So we walked up the outdoor staircases. For more reading in English, there is Adam Kaasa’s Appearing In or Out of Time and the February 2003 A+U.

Visit: Latin American Photography, 1944-2013

Caio Reisewitz, Casa Canoas (2013), courtesy ICP

Looking at photography, seeing design. The current exhibitions at the International Center of Photography are, of course, of photography, and brilliant, various and devastating images at that. But the work of contemporary photographer Caio Reisewitz and the collected works in Urbes Mutantes: Latin American Photography 1944-2013 also offer a showcase for design in multiple forms. Reisewitz’s large-format images (in whose size, as well as their greens and grays, you can see the influence of his study in Germany) represent “places of power” in Brazil, including Oscar Niemeyer’s Ministry of Foreign Relations in Brasilia. The moody image above is of Niemeyer’s own house in Rio, more commonly seen as a sunny, tropical tribute to the good life. A series of photocollages by Reisewitz introduce informal architecture into the green landscape, symbolizing the push of architecture against nature. His images seemed particularly a propos after reading Justin McGuirk’s survey of urbanism across Latin America in the new book Radical Cities.

Downstairs, the museum’s survey of Latin American photography is broken into themed sections, beginning with one on modern architecture. The New York Times has a thorough slideshow here. We see both the expected straight lines and sharp shadows, as well as more recent photojournalism on the decay and reworkings of modern housing. I was particularly excited by a huge vintage book, simply titled Caracas, on display in one case, as well as a one-of-a-kind album from Mexican architect Mario Pani’s office showing images of his CUPA housing. (I’ll post my own photographs of CUPA in its present-day state next week.) Several other sections of the exhibition also included beautiful examples of period book design, including a limited-printing automobile portfolio in a shiny stainless-steel case. Graphic design made an appearance not only in printed matter, but in a separate gallery on signs, documenting the work of sign-painters, advertisers and store-owners. Packaging turns up too: Susana Torres documents the sad end of the Inca-as-brand in a series installed floor-to-ceiling. There are more themes: identity, nightlife, protest, and many more photographers to discover. If you won’t be in New York before September, the catalog looks excellent.

Portfolio | Casa Prieto

While in Mexico City in March, I was also able to tour Casa Prieto Lopez, designed by Luis Barragan in 1950. The house is part of the luxurious suburb, master-planned by Barragan, called Jardines del Pedregal. The house was then for sale, with some (not all) of its original furnishings and artworks by Mathias Goeritz intact. It is far grander than Barragan’s own home, which is essentially on a townhouse lot. It also feels less fitted to the life of a particular human. One could intuit Barragan’s daily rituals from the spaces he made for them; the family Prieto had numerous children, and one imagined the architect leaving enough room between moments for their banging and flopping and wet feet. That last orange space is, of all things, the garage.

"Making something big happen at an urban scale is more than a popularity contest."

Did you know the Statue of Liberty was one of the first civic crowdfunding campaigns in America? This piece of century-old news made the rounds last year, as readers rediscovered the central role of Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World in raising $100,000 ($2.3M in today’s dollars) to fund the pedestal to receive Lady Liberty in 1885.

As MIT researcher Rodrigo Davies pointed out then, and does again in his recent thesis on civic crowdfunding, it wasn’t just the five-month, centrally organised campaign that makes the Statue a historical precedent. Rather, it was the skilful way Pulitzer’s paper made it seem as if everyone were donating, with daily updates, a reward system, and personal anecdotes underlining the idea that no amount was too small. The World also used anti-elite sentiments to rally the working classes to the cause – traditional, big-donor fundraising hadn’t closed the gap on the pedestal’s cost – mentioning donors by name in daily updates, and used the platform of the newspaper to make the campaign appear to be ongoing national news. Social media requests for backing, frequent emails once you have given, a commemorative tchotchke once it’s all over: all news from 1885.

On X

Follow @LangeAlexandraOn Instagram

Featured articles

CityLab

New York Times

New Angle: Voice

Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness