A Lazy Man's Way

Almanzo asked Father why he did not hire the machine that did threshing. Three men had brought it into the country last fall, and Father had gone to see it. It would thresh a man’s whole grain crop in a few days.

“That’s a lazy man’s way to thresh,” Father said. “Haste makes waste, but a lazy man’d rather get his work done fast than do it himself. The machine chews up the straw till it’s not fit to feed stock, and it scatters grain around and wastes it.

“All it saves is time, son. And what good is time, with nothing to do? You want to sit and twiddle your thumbs, all these stormy winter days?”

“No!” said Almanzo. He had enough of that, on Sundays.

From ‘Farmer Boy,’ by Laura Ingalls Wilder.

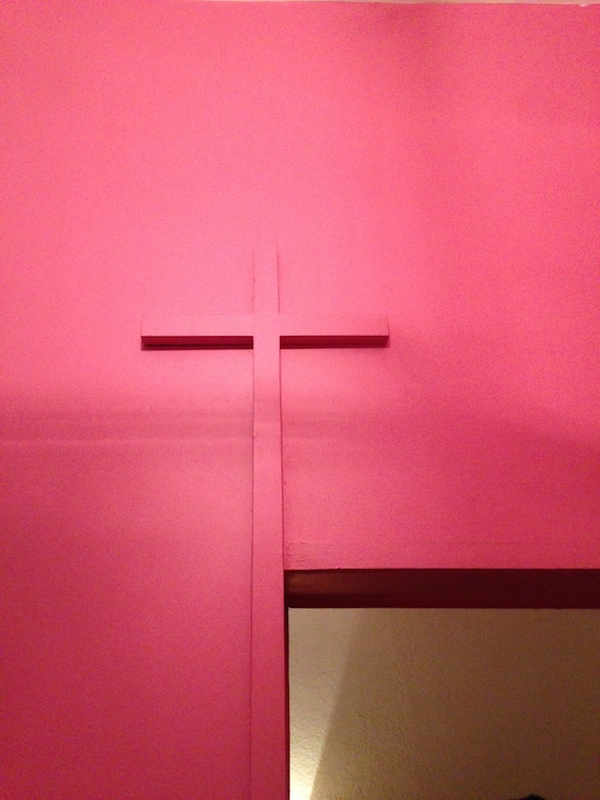

Portfolio | Barragan House

I visited Luis Barragan’s house in Mexico City in March. Inspired by Guy Trebay’s Travel story on visiting Barragan, a portfolio of photographs from that day.

Who Pays for the Picture?

Zaha Hadid, Heydar Aliyev Centre, Baku. Photo: Iwan Baan, 2012.

The Harvard Design Magazine relaunched at the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennial with an issue titled Do You Read Me? I contributed this short essay to the Artifacts section.

In late 2013, the White House Correspondents’ Association (WHCA) wrote to White House Press Secretary Jay Carney, protesting its photographers’ lack of access to presidential events. Few people would have noticed—images from these events had circulated via social media. But most were the work of a single photographer, Pete Souza. As the official White House Photographer, his images are often the only documents of historic moments.

“You are, in effect, replacing independent journalism with visual press releases,” said the letter. “Visual press releases” grabbed my attention. What, ultimately, are the majority of the architectural images we consume? Many blogs and magazines feature images by photographers hired not by the publication, but by the client or designer. A striking image used to illustrate a review of the building can become the trademark for that building or an architect’s practice. These pairings demonstrate a disconnect between the processes of making the content we read and that which we see.

Visit: Tara Donovan at Pace

Tara Donovan has been exploring the topographic possibilities of everyday objects for some time, but each new arrangement feels like a surprise. I loved both her mountain range and cumulus of cups. At Pace Gallery in Chelsea, through June 28, you can see what she can do with index cards and cocktail stirrers. I found the wooly piece pictured above reminiscent of the work of Warren Platner, with its whiskey tone and Sputnik heredity.

Four Building Toys for the Ages

We have a lot of building toys. When you are an architecture critic, married to an architect, people tend to give you one set after another of blocks. Soft blocks, wood blocks, blocks that snap together, blocks that all fall down. After the blocks they give you joints. Ball-and-socket joints, hub-and-spoke-joints, articulated joints. And then the brands rush in, and they give you Lego. Star Wars Lego, Ninjago Lego, Chima Lego, Lego knock-offs that light up. I await the onset of the programmable. We’ve already entered the realm of the digital, via Minecraft and the delightful Toca Boca apps.

I’ve now lived with these sets for five years. Here are the four that still get played with almost every day. All plastic, as it happens. Despite the modernist fetish for wooden toys, plastic is lighter and creates easier attachments, two aspects that have proved important to my kids. I’ve arranged the toys in the order you might consider purchasing, starting at age 2.

1. Duplo

As I wrote in Living in Lego City in 2012, Lego proper offers a limited number of scenarios, the sets dividing starkly into those “for girls” and those “for boys.” Duplo, sized for smaller hands, suffers no such split personality. There are house sets and vehicle sets, which offer up useful pieces of domesticity like beds and fences, and transportation options like wheel bases. If you are lucky, as we were, you can score a hand-me-down bin of blocks, in rainbow colors, and a set of different-size platforms. My son began building on those platforms at age 2, and he hasn’t stopped. We’ve made houses and Bat caves, the High Line and garages, skyscrapers and mazes. Even though we now have Lego proper, the kids return to the Duplo for its scale and speed. You can throw something together in a minute to house a superhero action figure, or make a sketch of a city as backdrop.

2. Tubation

When we got Tubation as a gift I sort of shrugged. Was it a bath toy? An instrument? We weren’t ready yet for a marble run. But then my son got his hands on it and better things happened. (Sometimes we lose imagination as we age.) Swords, dinosaurs, canopies, bracelets and, yes, a gun or two. Even little hands can put the tubes together and take them apart, and their gross scale makes it easy to create child-size tools. There are specialized sets with instrument add-ons, marble slots and transparent tubes but those are hardly necessary. This toy is like the stick of building toys, and it is inexpensive too.

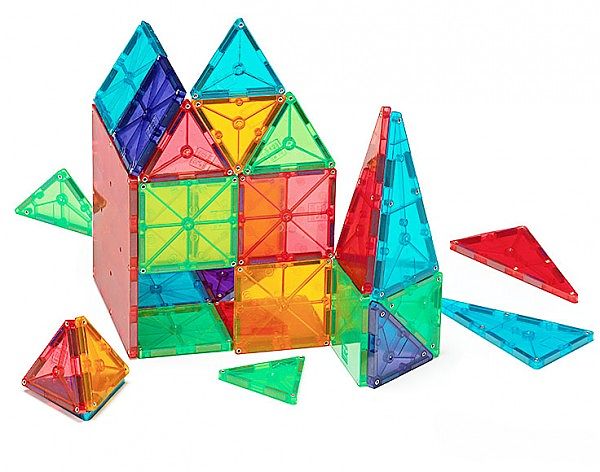

3. Magna-Tiles

This is an expensive toy, about $1 per tile, but I’ve recommended it over and over. We now have 300 pieces, through a combination of gifts, hand-me-downs and purchases. At times, when the castle turned into a skyscraper that needed a multilevel garage that stretched across the windowsill, we needed even more. Magna-Tiles are easier than Lego, and you can make something tall and beautiful in a flash. As kids get older, they move beyond the basic squares (in two sizes) and start thinking about the possibilities of the triangles, matching them into squares when they run out, creating geodesic hovercraft, bugs, spaceships. They teach the possibilities of geometry, and anything you make, even a little 2yo cube, looks beautiful. Since these things tend to hang around, it is nice when the creations are as good as sculpture.

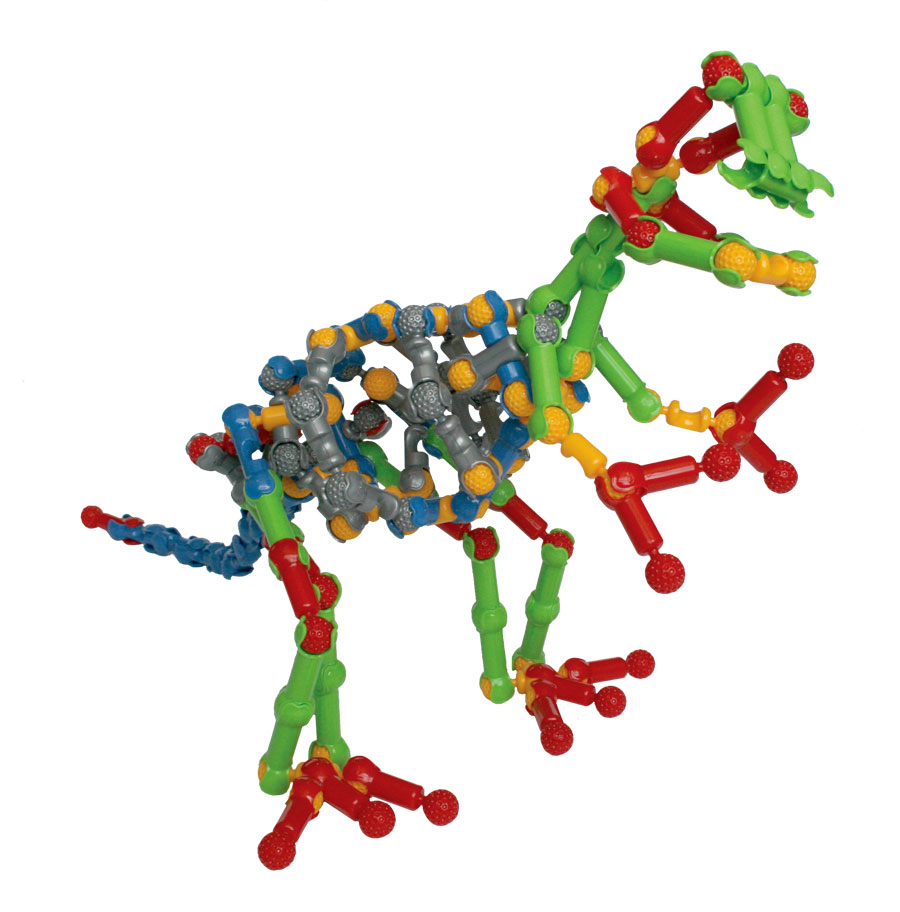

4. Zoob

Zoob comes with directions: totally unnecessary. Zoob is a set of plastic ball-and-socket joints that can be combined in various ways. They are easy to snap together (though hard for little ones to pry apart). If Duplo and Magna-Tiles suggest houses and vehicles, Zoob suggest creatures, manipulable skeletons that can switch from insects to dinosaurs to men in just a few clicks. I’ve been amazed to walk into my son’s room and find the floor suddenly covered in alien beings. The largest is always the leader, simplistic babies in the corner, and something new being hatched out of the pile in the center of the room. Because the individual pieces are small (but not so small as to be choking hazards), the range of possible scale is terrific. As with these other toys, you can watch the progression of your children’s imagination through the increasing number of possibilities they see in the toy.

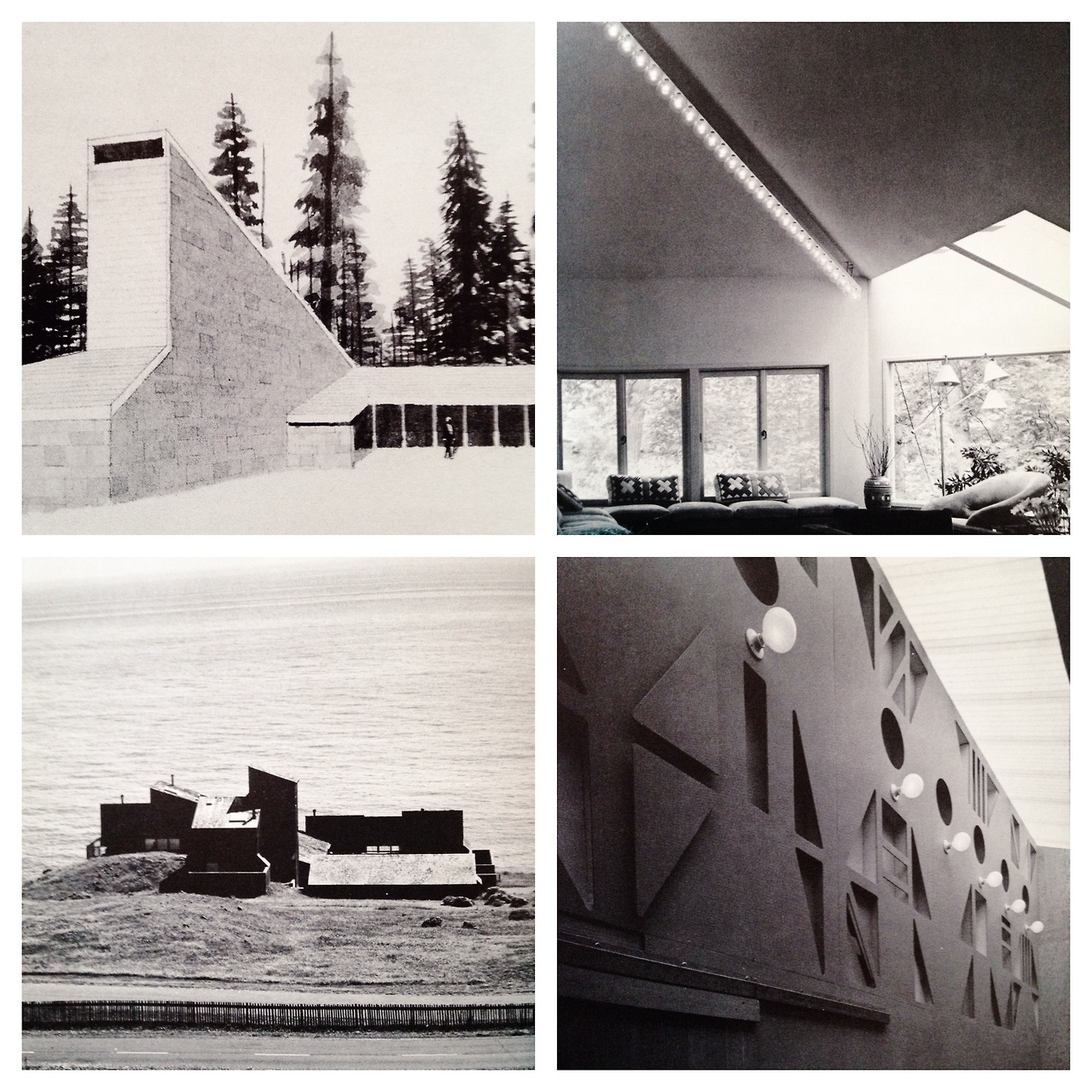

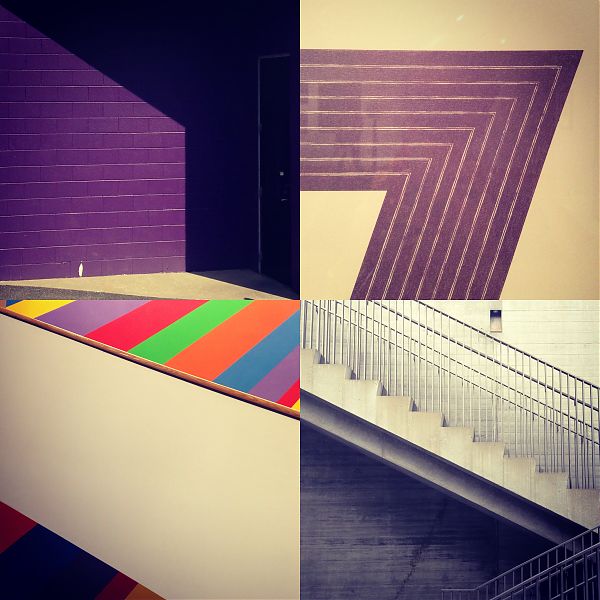

100 Days of #PicFrame

When I got back from Mexico City in March I felt energized. Every day of that trip brought new wonders, colorful, architectural, transportational. I had so many photos I was forced to PicFrame them, creating small digital collages that pointed to the overlaps and contrasts in the floors, walls and structures we saw. Travel forces me into a higher state of noticing, and I wanted to bring that energy back to my own city (or rather, cities, as I was then in the last months of my Loeb Fellowship). Inspired by Michael Bierut’s 100 Days assignment, I assigned myself to make a PicFrame each day for 100 days, using photos taken that day, hashtagging them #picframeaday on Instagram and Twitter, and storing the whole set on Tumblr.

I made it. Yesterday was my 100th PicFrame. Today I am going to rest, though I am thinking about a new assignment, and open to suggestion.

What did I learn?

Some days are bursting, some days are not. I tend to alternate between days at my desk, getting to 1000 words (the average length of one of my draft essays), and days out and about, going to sites, traveling between Cambridge and New York, visiting parks. Some PicFrames are packed with interesting architecture, and some are made of up things around my house. But I enjoyed looking for those patterns, joined by theme (City) or print (Marimekko) or color (red). It was even more fun to look for patterns in other people’s houses (green).

Some days I only saw one thing I wanted to photograph. Those desperate days, however, provoked more creativity on the app end of things, resulting in pinwheels and stutter-steps that were as interesting as a 3D effect. Monkeying with its frames, rules and effects was also instructive, and inspired my 6yo to make PicFrames too (albeit with more radical image manipulation, and nonsense captions).

Old is OK. I felt guilty when I went to the archives, online, in books, but the response to those PicFrames was often more enthusiastic than to some other experiments.

Even when you set your own homework, you still feel guilty. So I will confess to you: I cheated on the assignment 1.5 times. One Friday I spent all day on the train, when the day before I’d seen a number of amazing modernist sights. I was tired and grumbly, so I posted Breuer the day after I photographed it. One Sunday I photographed some things around my house, then happened upon a better visual idea. I used them the next day, but felt too silly photographing them over again.

Above all else, the exercise confirmed what my eye is drawn to. Mexico City had it in spades, but bright hues, contrast graphics, and intense texture are also to be found up north. I felt on my toes the whole time, which refreshed some commonplace walks, and inspired me to take detours. Whatever visual task I give myself next, it has to provide the same prompting to look at my life a little more closely, if not necessarily in squares.

Glass House Stages Fujiko Nakaya's "Veil"

Credit: Richard Barnes

There are dandelions on Philip Johnson’s lawn. It is thick and green, mown on a diagonal following the gravel paths between the Glass House and the Brick House in New Canaan, Conn. But still, dandelions! Interlopers into this realm of single-material planes. I can’t help but imagine Johnson pointing a bony finger at the yellow flowers, leading to their immediate beheading.

I’m here to see a different kind of interloper: the first site-specific artwork to engage Johnson’s iconic 1949 house. Unlike the dandelions, it’s the perfect modernist houseguest. No muss, no fuss, no smell. Fujiko Nakaya’s “Veil” manages the difficult trick of creating a new frame for a familiar architectural monument (think of James Turrell at the Guggenheim Museum, on a much larger scale), while leaving only a spatter of raindrops on the landmark. “It alters it greatly but only momentarily,” says Glass House Director Henry Urbach.

I am a GIANT on Section Cut

A few weeks ago, Dan Weissman and Kyle Sturgeon of the design resource blog Section Cut came to interview me at Doebele House in Cambridge, semi-official home of the Loeb Fellowship. We had a great conversation about my life as a design critic and its many way stations. That interview, edited for length, is now available on their site. You can listen or download it here.

During the conversation, she shares some best practices and sheds perspective on her journey to becoming an influential architectural critic, journalist, and social media maven with over 10.4k Twitter followers to date.

Though not explicitly a designer, Lange’s work takes a critical eye to the built environment, design culture, and our fields’ positions relative to contemporary societal concerns. This work is executed with such care and precision that she is often invited to speak at prestigious institutions and write for some of the most respected publications in the world. And, even with such accolades as these, Alexandra manages to be unpretentious, approachable, and generous enough to sit down and talk with the likes of us.

Take a listen above to see what we mean, and make sure to explore some of Alexandra’s top resources below. Consider her challenge posed to Team Section Cut – GAME ON!

Among those resources: Lydia DePillis’s Tumblr 100 Percent Men, Ada Louise Huxtable’s On Architecture, Nicholson Baker’s The Mezzanine. No excuses, especially since a used copy of On Architecture is a mere one cent.

Social Media for Architects in Five Easy Steps

On May 22 I participated in the panel More than 140 characters: social media + architecture at the Boston Society of Architects. You can read a write-up of the event on the Payette blog, More than what you ate for lunch. For everyone else, here’s what I said were the three reasons architecture needs social media, and the five things architects should be sharing.

In January, I made fun of Bjarke Ingels’s Instagram. After my article was published his Instagram went dark for a few weeks, but then it started up again. When I checked in on it in May, these were his last few posts: blurry photo of New York City from a plane, BIG’s LEGO House project rendered in LEGO, construction selfie, Bjarke and Martha. So basically, more of the same.

The only signs that he might have listened to me were a newspaper clipping from his childhood, heralding the first design competition he won, and a nice, clear photograph showing the first few completed stories of his building on West 57th Street. The first nods to an Instagram hashtag game known as Throwback Thursday (#tbt) – everyone posts embarrassing photos from their youth – the second provided insider news on one of his projects from an angle most of us can’t get. They show understanding of how social media can be used for conversation, rather than simply self-promotion, and how it might illuminate the life of the working architect in useful ways.

As I said then: you don’t want to be boring, do you? I’m going to use my ten minutes to explain why architecture needs social media, and to give you some ideas of ways to get started. It’s also supposed to be fun. If Twitter is a chore on your to-do list, you’re doing it wrong. Social media should have personality and playfulness, introduce you to new people and let you see new things. Let me try to explain how.

Why architecture needs social media.

Because people don’t understand you. What do architects do all day? Nobody knows, least of all your clients who probably think they pay you too much, when the opposite is true. Judging by the movie portrayal of architects, they are men, who are sensitive, who design pretty houses, who wear white shirts and carry rolls of drawings. Social media offers an opportunity to show and tell more. Not your lunch, but the sketch you made at your meeting. Not your shoes, but the new paving that just went in. Whether with pictures on Instagram or words on Twitter, you can provide signposts.

Because you are at your desk all day long. Many architects spend all day at their desks, just like writers. For you, social media can become the water cooler. What are people talking about, not just in architecture, but in culture? What are people buying, making, cooking for dinner? You need to stay connected to wider streams, streams that are broader than the architecture magazines you subscribe to. Your family needs you to have good ideas for meals as well as flashing details. Social media has the right mix of high and low to allow you to dip in.

Because architecture should be part of the conversation. Which conversation? All of them: news about cities, news about culture, news about Mad Men. (I laughed out loud on the Sunday when one character gave another an Erector Set, “America needs engineers,” he said.) Architects have a specific lens on all sorts of projects and prospects for the future, and by meeting their audience where they are – hanging out on Twitter, posting vintage architecture photos on Instagram – you can add that perspective.

What architects could share on social media.

1. Self-promotion. I know, I said you shouldn’t do this, but really, you shouldn’t do this too much. One quarter to one third of your posts should be about the lectures you give, the awards you win, the projects you complete. Try to make those posts useful: link to the video or the live feed, to new construction photos, to the list of everyone who won. People wouldn’t follow you if they weren’t at least somewhat interested in what you do.

2. Influences. What building did you make a pilgrimage to on your last vacation? What new design book did you buy? What classic text are you listening to on audiobook while you draw up that set? Do you have a real inspiration wall? An inspiration tote bag? All of these are interesting to other people – really – and tell us more about what goes in to your design. It’s also a chance to tip your hat to what you consider excellent in other fields. Or even your own. It would be nice if architects could compliment each other.

3. Details. When I started talking about architects using Instagram a friend joked that her feed would just be handrail details. Every time she goes to a museum, a park, a transit hub, she is checking out the hardware and the miter joints. Well, I responded, that would be a great Instagram feed. Obsessions, rendered in artistic photos, are just what Instagram was made for. It’s no sillier than bouquets or fancy coffee foam. Show us the city (or the country) through the eyes of the architect. It’s funny what you can become known for. I get tagged for anything Marimekko, and outrageously bright floors. What aesthetic choice would you like to be known for?

4. The critique. What needs improvement? Show us that sad public space, that neglected modern monument. Think about what architecture can do and show us where it is needed. Maybe such a project is beyond your scope right now, but by sharing it, thinking about it, making digital connections, you may be able to expand your territory.

5. Protest. We make architecture. Can we also protect it? Architects need to be out in front articulating what can be saved and why. Social media gives you a platform in the larger marketplace of ideas to share what’s important over the long term.

On X

Follow @LangeAlexandraOn Instagram

Featured articles

CityLab

New York Times

New Angle: Voice

Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness