Meet Me by the Fountain in Paperback, Dec. 5

The paperback of Meet Me by the Fountain will be published on December 5! All the same content in a new, more portable package. It makes a very meta holiday gift.

I’ve been doing a bunch of publicity in support of the launch, including this story at Bloomberg CityLab, and radio interviews at Marketplace and Today, Explained.

Was also thrilled to see it on the New York Times Book Review’s recommended Paperback Row.

Toronto’s Answer to Hudson Yards Looks a Lot Like a Mall

The canopy at The Well, Toronto. Photo courtesy RioCan.

Friction is the enemy of shopping. Out of stock, out of your size, check another department. Go upstairs, go downstairs, go to the other store. Can’t find a sales associate, can’t find an open register. More recently, closed anchors and empty storefronts have emerged as obstacles to the trance-like state that retail stores hope to induce in consumers. There’s even a name for this effect: the Gruen transfer, after Victor Gruen, the father of the shopping mall.

But the first point of friction for any retail establishment is simply getting them in the door. Revolving or slider? Heavy or light? Push or pull? Neither shopper nor seller likes being embarrassed by a portal.

Imagine my surprise and delight when I walked up to The Well — a seven-building mixed-use retail, residential and office development in the heart of Toronto — and found it had no front door at all. I walked under the boxy overhang of the project’s sole office tower (1.2 million square feet) and into a 36-foot-tall forest of fat concrete columns. Beneath my feet the pavement changed from a concrete grid to a dappled pattern of smaller granite blocks, opening into a 320,000-square-foot retail space enclosed by a German-engineered glass canopy three stories up.

Remembering Jean-Louis Cohen

Disney Concert Hall tour in February 2003, I am third from the right, JLC far right. (Photo Courtesy Karen Leader)

Curator, architect and historian Jean-Louis Cohen died suddenly in August. Along with his many international accolades and accomplishments, he was also my dissertation advisor at the Institute of Fine Arts and, latterly, a friend. I contributed this short memory to a collection of memorials published in The Architect’s Newspaper.

The death of Jean-Louis Cohen has been a shock and a deep sadness. I had not seen him in person since the beginning of the pandemic, but it was one of the delights of adulthood that someone so smart, so connected, and, as a 25-year-old master’s student, so intimidating, could eventually morph from a teacher into a mentor into a friend.

I and several of my classmates in my IFA cohort are small women; when we first started at the Institute, I imagined us as ducklings following behind Jean-Louis. The dramatic West Coast version of this dynamic was captured in a Los Angeles Times article about a field trip he took us on to Los Angeles, perhaps his third beloved city after Paris and Casablanca. On that trip, our buttoned up, urbane advisor revealed himself to have a California persona—open collar, sportscar—and the rest of us, packed into minivans, could only rush across multiple lanes of traffic to catch up as we zig-zagged up and down the coast from Eames to Wright to Schindler to Gehry. I had never been to L.A. before and I still remember standing in the mirrored bathroom of John Lautner’s Sheats-Goldstein house (the original Cocaine Décor) and thinking, Where am I? Where has this been my whole life? I hadn’t even known this kind of architecture existed, and it took a middle-aged Frenchman to show it to me. Jean-Louis didn’t want us to follow—he wanted us to catch up and, thanks to his tutelage, we eventually did.

When I began the MA program at the IFA, I had already been working as a journalist for four years. My plan was to get a PhD and then use that knowledge to support my work as an architecture critic. I didn’t realize then how unusual it was within academia, and especially during that era of the Institute, to encourage public scholarship. But Jean-Louis enthusiastically supported the notion of writing for mainstream media, and demonstrated, through his own writing, curation, friendships, and choice of topics, that engaging with the broadest possible public could be the core of the intellectual project.

His own work often took a topic that had been covered a million times—postwar architecture, Le Corbusier, Frank Gehry—and demonstrated that there were plenty of new things to say if you (he) looked at it from a different angle. Even though he spoke more languages, knew more cities, and had already published more work than most of his advisees ever would, he took our interests and ideas seriously, asking questions, asking us to be more provocative, and never herding us back toward some imagined safe architecture history. A radical proposal didn’t necessarily mean going to the ends of the earth but deep into the archives, interrogating the dominant perspective, politics, or value systems. My dissertation, which he enthusiastically supported, was on the surface about postwar corporate architecture, the most heroic and bureaucratic of topics, but ended up launching my ongoing research interest in collaboration and personal networks. Classmates wrote about sculpture, vernacular architecture, technology; there was never one dominant period, geography, style, or discipline for the dissertations his students wrote. He didn’t care about that kind of limit, or reputation management, or reflection, and he empowered all of us to ignore those terms as well.

Downtown Brooklyn Gets the Gotham City Treatment

The Brooklyn Tower, photographed by Max Touhey for SHoP

On an overcast day, the delicate pointed crown of the Brooklyn Tower is invisible in the clouds, as if a vengeful enemy has shrouded its superlative vantage in smoke. Nonetheless, over the low-rise flatlands that comprise most of the borough, the jagged edges rising along the dark shaft are present and unmistakable.

The Batman building, the Tower of Sauron — the nicknames write themselves. And why not? Better this than another squared-off tower that simply fiddles with the ratio of white solid to blue glass. Maybe I should hate it for its bigness, its blackness, its thrust — but I don’t. Skylines need punctuation. The designers of the Brooklyn Tower, SHoP Architects, threw everything at this to make it an exclamation point.

The Brooklyn Tower towers over the rest, a 1,066-foot-tall fortress at 9 DeKalb Avenue that marks the borough’s first foray into the supertall stratosphere. Yet it is not completely alone in altitude: Downtown Brooklyn has added more than 20,000 housing units since it was rezoned in 2004, most of them in undistinguished high-rises. Exceptions include Studio Gang’s 11 Hoyt and Alloy LLC’s forthcoming 100 Flatbush, which also play with texture and technology in ways that reference the 1930s — New York’s first great skyscraper age.

Love and Lattes

How the Coffee Shop AU feeds romance.

Herb’s Electronics is a coffee shop. It is, specifically, a coffee shop in Nashville, which kept the name of the previous business because its new owners don’t want to pay for a new sign. It’s confusing, I know. Plenty of patrons have complained to its staff of reliably snarky (and buff) baristas, but Herb’s Electronics is not a real place. It’s a Coffee Shop AU, or alternative universe, in fanfiction parlance. AUs are stories in which people or characters famous for something else—being superheroes, singing in a boyband, solving mysteries, turning into werewolves—are transported into another world. They may live as high school students, run from zombies, dance in a Regency ballroom, or, in the case of Herb’s Electronics, fall in love at a coffee shop.

In this particular Coffee Shop AU, written by Archive of Our Own (shortened as AO3) user McSpot, fictional versions of real hockey players are baristas, bakers, stockbrokers, and sometimes even hockey players. Over the course of four works, written in 2018 and 2019, Herb’s Electronics’ owners, employees and customers find love, both romantic and platonic, and turn the coffee shop into both a successful business and an alternative family. It’s like a giant latte with a heart of foam—just what the readers, and writers, of the 34,812 works tagged “alternative universe—coffee shops & cafes” on AO3 are looking for. I count myself as one of them.

Some Old-Fashioned Home-Design Manuals Are Worth Revisiting

In 1868, the designer Charles Eastlake published “Hints on Household Taste,” a popular guide to outfitting the home in good taste, from the street front to the china cupboard and all the rooms in between.

In his introduction, rather than taking a supportive tone, he chastises the reader. “When did people first adopt the monstrous notion that the ‘last pattern out’ must be the best? Is good taste so rapidly progressive that every mug which leaves the potter’s hands surpasses in shape the last which he moulded?”

“He blames it on the housewife,” said Jennifer Kaufmann-Buhler, the author of “Open Plan: A Design History of the American Office” and an associate professor at Purdue University. The message is, “Women have terrible taste, and we need to correct them,” Professor Kaufmann-Buhler said, adding that she does a “very lively reading” of the passage for her students, “annotating it in real-time in an over-the-top British accent.”

Despite Mr. Eastlake’s seeming disdain for the clutter-mad housewives of the Victorian era, his “Hints” did provide a template for 150 years of house books. Every season brings out more manuals of household taste, from glossy-page inspirational books suitable for coffee-table display to chart-heavy how-to guides, with diagrams of immaculate closets and formulas for D.I.Y. cleaning products.

Anna Wagner Keichline: A Legacy of Invention

In the penultimate episode of New Angle: Voice, Season 2, meet Anna Wagner Keichline, architect, inventor, suffragette, and loyal daughter of Bellefonte, Pennsylvania.

Nineteen-thirteen was the year of the grand march for suffrage in Washington DC, where the 250,000 marchers and attendees eclipsed coverage the following day of the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson. Bellefonte PA, population 4,216, had its own march, on the Fourth of July. Costumes were de rigueur, with a goodly number of stately toga-clad ladies and a few wild harridans on horseback, along with one intrepid girl in her Cornell cap and gown: Anna Wagner Keichline.

Not every architect has the opportunity to build skyscrapers. In Bellefonte, Anna used her talents to improve the lives of her neighbors by designing their houses and gathering places. She adopted a gently accommodating architectural style in the shadow of all that high Victorian tracery, and designed sturdy churches, theaters, homes, schools, and recreation facilities in her hometown that still stand well and firmly in their context. But on her own time, she experimented with the latest technologies, eventually earning seven patents on inventions ranging from a fitted kitchen to a modular concrete brick.

Decoding Barbie’s Radical Pose

Illustration by Tim Enthoven

The “Barbie” movie glides over the history of dolls as powerful cultural objects.

In Barbieland, as envisioned in “Barbie,” the writer-director Greta Gerwig presents a world where positions of power are held by female dolls such as a Black President Barbie and a Filipina American Supreme Court Justice Barbie. Indeed, in the pink landscape of “Barbie,” all the jobs are held by women, and the Dreamhouses are owned by them, too; the Kens are mere decoration until one of them catches a glimpse of men’s lives in the Real World. But, by making patriarchy the villain of the story, the movie glides over the decades in which Mattel, the company that makes Barbie, waffled on racial representation and the depiction of women’s professional roles. “The Barbie world you see in the film is Malibu Barbie from 1971,” Rob Goldberg, the author of the forthcoming book “Radical Play: Revolutionizing Children’s Toys in 1960s and 1970s America,” says, “but, in reality, the racial diversity of the Barbie character wasn’t there yet.”

Goldberg’s book describes how toys became political during the sixties and seventies—from Lionel Corporation’s toy trains’ embrace of anti-violence rhetoric to wooden figurines that allowed children to assemble families more complex than a husband, wife, and two kids. American culture was convulsed by Vietnam War protests, Title IX disputes, and the Equal Rights Amendment debates, and toys were enlisted in the fights for empowerment and equity by women and people of color. Gerwig’s film builds upon, but only occasionally acknowledges, sixty years of attempts to use the popularity of Barbie to advance a more complex agenda than sun, fun, and lots of pink. That’s too bad, both for the historical record and for the new buyers of Barbie that the film’s success will attract. As Goldberg writes, the nineteen-sixties forced toy-makers “to publicly reckon with, perhaps for the first time, their status as entrepreneurs of ideology.”

Malls across the U.S. transforming amid rise of e-commerce

Across the United States, some malls are undergoing big changes. Businesses such as animal shelters, trampoline parks and movie theaters are filling the spaces that have been left empty in recent years. NBC News’ Brian Cheung interviewed me for the evening broadcast.

Review: Alexandra Lange on Danish Modern

My childhood best friend’s dining room hosted a suite of matching wood furniture: a tall glass-fronted sideboard; a table that stored its extra leaves below the surface, to be pulled out like drawers; chairs with open backs and black leather seats, all in a mellow amber tone. As she moved across the country, and up the West Coast, a coffee table moved with her, worth the trouble because, from the eighties to the aughts to the 2020s, it remained in style, as suited to a brick Colonial Revival home in Durham as it was to a PNW Craftsman.

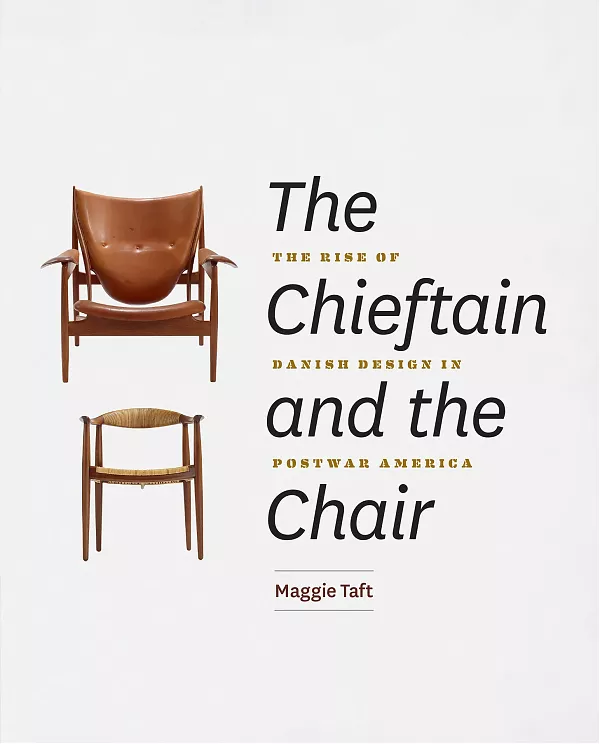

This was intentional: From the moment such furniture appeared on American shores in the 1950s it was advertised as “address[ing] the needs of younger couples and new households, with its cleanliness of design.” Its “soft, rounded flowing forms” evoked the craftsmanship of an earlier era, while its “tapered lines” indicated to the world that you weren’t stuck in the past. While the style first drew attention in 1949 with a pair of chairs—the Chieftain, by Danish architect Finn Juhl, and the Round Chair, by Danish furniture designer Hans Wegner—when American manufacturers got done with it, you could buy a recliner, a stereo, a television, in still-desirable, still-salable Danish Modern. The authorship and by and large the artistry of the original chairs was effaced by the wave of cheaper, mass-produced copies, many of them made by American manufacturers, for American homes, with only the lightest sprinkling of Danish-ness.

In her new book The Chieftain and the Chair: The Rise of Danish Design in Postwar America, Maggie Taft sets out to tell the story of how we got from the 1949 Cabinetmakers Guild Exhibition in Copenhagen, where Juhl showed his chair, with its shield-shaped back, next to a pinboard of influences including a bow and a photograph of an African hunter with spear (Juhl’s “romantic—and colonizing—view of primitive authenticity”) to the handsome, if slightly generic, coffee table in my friend’s living room.

On X

Follow @LangeAlexandraOn Instagram

Featured articles

CityLab

New York Times

New Angle: Voice

Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness