A Sherbet-Colored Experiment in Cohousing Outside of Boston

Photo: Naho Kubota; Illustration: Stephanie Davidson

When the architects of Bay State Cohousing first approached the challenge of designing a new residential project for Malden, a city in greater Boston, their first job was trying to fit a new 45,000-square-foot housing development into a neighborhood laden with older buildings.

On one side of the site sits a Richardson Romanesque-style office building, with deep red brick and arched windows; across the street, there’s a turn-of-the-century stone church. Nearby are lots of typical Boston single-family homes, with gable and mansard roofs. The newest addition to the neighborhood, designed by the studio French 2D, splits the difference between the 19th-century grandeur and welcoming porches of those historic styles nearby.

“Our first design was almost Safdie-like, with pixelated terraces,” says Jenny French, referring to Moshe Safdie’s Habitat ’67 in Montreal. “We also tried it as a Dutch village with a mansard roof. But we ended up with a friendlier version that’s like a rambling New England house of additions.”

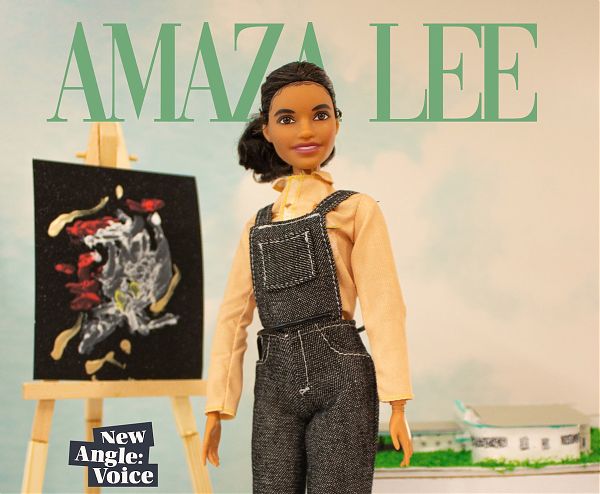

Amaza Lee Meredith: Love and Home

In our third episode of Season 2, meet Amaza Lee Meredith: architect, entrepreneur, queer Black pioneer.

From the introduction by producer Cynthia Phifer Kracauer, who has also been making custom Barbies for each of our podcast subjects:

I picked up a free glossy real estate magazine with an enticing photograph of summer leisure pursuits under the title “Sag Harbor: A Whale of a Good Time.” We traveled out there in early spring, collecting voices of preservation, community, celebrity, and long tenured summer families as we searched for Amaza Lee Meredith’s modern architecture. A short bike ride away from the summer haunts of Melville, Steinbeck, Betty Friedan, Spalding Gray, lived the creator of Azurest North, the Black summer real estate enclave syndicated by Amaza Lee Meredith with her sister Maude Terry. But on the beach we found only Maude’s name enshrined on the commemorative plaque.

For a Selfie (and Enlightenment), Make a Pilgrimage to Bridge No. 3

Illustration by Sam Pease

There’s often more to Instafamous infrastructure than meets the eye.

The first birds returned in the spring of 2022. First it was just a few scattered families: black coats, colorful heads, chirping in an unknown language. As the weather warmed, the visitors shed layers, their plumage brightening. They landed in groups, fledglings in tow. They came as singles, stretching and preening in the sunshine. They came in pairs, taking turns being the center of attention. Alighting, fluffing, resettling in a more comfortable position. Observation seemed only to make them more comfortable, as if their natural habitat were the backside of a smartphone.

Although Brooklyn Bridge Park sits on the Atlantic Flyway and plays host to more than 120 species of birds lured by its wetlands and piers cultivated with native plants, the birds I speak of here are the Instagrammers. In the depths of the pandemic, as I took my daily walk through the linear landscape, I passed real birds and local birdwatchers moving through the park in morning waves, cheeping in the underbrush, settling on the spindly trees, posing on the pylons of a ruined pier. In the afternoon the prime movers were joggers and cyclists; on weekends particularly scenic spots—the glade north of Pier 2, the deck underneath the Brooklyn Bridge, the arches at St. Ann’s Warehouse—would host parties of more exotic plumage. Brides and their clutches of bridesmaids in champagne or mint, groomsmen in matching ties. A teen decked out for her quinceañera, her dress almost as wide as she was tall. Less often, on one of the slowly greening slopes, an engagement picnic set up with the Manhattan skyline as backdrop.

What New York’s Cave-Like Natural History Museum Misses About Nature

The immersive Invisible Worlds exhibition. Photo by Ismail Ferdous / Bloomberg

Under the vault of the 1936 Theodore Roosevelt Rotunda, the eager young archaeologist exploring Manhattan’s American Museum of Natural History meets Barosaurus and Allosaurus, skeletons cast in a frozen prehistoric battle.

Inside the enormous glass box of the 2000 Rose Center for Earth and Space at AMNH, the avid young astronaut finds the 87-foot-diameter fixed sphere representing the sun.

And between the gray canyon walls of the 2023 Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation at AMNH, the keen young entomologist encounters (finally!) signs of life. Tiny signs: the mesmerizing up-and-down procession of leafcutter ants dining on magnolia and forsythia in a habitat of glass and steel.

Designed by Studio Gang, the new $465 million, 230,000-square-foot Gilder Center looks like caves carved not from bedrock but out of Bedrock. Through its irregular openings, visitors will witness more movement — of people moving vertically up the central bank of sittable steps or crossing the void on a bridge reminiscent of a Brontosaurus neck. Beyond that, a thousand butterflies flutter in the second-floor vivarium. A little farther into the shadowed voids visitors will discover Invisible Worlds, a 12-minute immersive projection which splashes undersea creatures and brainwaves and visualizations of DNA across the walls and floor — all as if to say, take that, Van Gogh!

The Cannabis Edible Goes Mainstream

Illustration by Nicholas Konrad / The New Yorker

Amid the legalization of marijuana in many states, designers are working out how to sell edibles to a new generation of consumers.

For the past decade, the pinnacle of California package design has been the Apple box, with its minimalist exterior, layers of white-on-white fittings, and glossy tech product encased within. Sleek, seamless, promising you the world—made in China, designed in California—at the swipe of your fingertips. But recently a different industry has taken over innovation in hand-held products. An industry interested in local. An industry interested in social. An industry interested in taking you on a surprisingly autobiographical trip.

I speak of cannabis, now legal for recreational use in twenty-one states and D.C. The cultural handoff from high tech to high times seems just right for our not quite post-pandemic moment, with its halting return to IRL encounters, its panoply of stressors, and its personal branding of everything. Growing the cannabis market, however, has required repackaging a product that originally came in generic plastic bags and rolling papers, in varieties that were named for a location, an aroma, or an in-joke. Things have become a little more complicated now that cannabis is legit and you are selling a product in a palm-size package, from dispensaries that cater to millions of newbies.

The Art We Must Live With: Ada Louise Huxtable and Architecture Criticism

The second episode of Season 2 of New Angle: Voice brings you a closer look at the life and career of Ada Louise Huxtable, the first architecture critic for a daily newspaper, and the first winner of the Pulitzer Prize in Criticism.

General readers are quite accustomed to having their choices in books, films, dance, opera, drama, TV, and music directed and influenced by critics’ opinions. We find our favorite interpreters, trust their judgement, buy books or tickets. But in the concrete jungle of the city, we are captives, we have no choice to ignore what is built by others to house us, for our work places, our transit systems, our public realm. The ubiquity of mediocre architecture dulls the senses, and yet, when architecture achieves greatness it can exalt the human spirit. Ada Louise Huxtable set out to separate the dull from the great. A few architects tried to argue with her. They never won.

Special thanks in this episode to the generous architectural critics: Cathleen McGuigan, Christopher Hawthorne, Julie Iovine, Karrie Jacobs, Christine Cipriani and Paul Goldberger, following the inimitable example set by Ada Louise. Thanks also to architectural historian Meredith Clausen, Wall Street Journal arts editor Eric Gibson, the Huxtable archive team of Stuart and Beverly Denenberg, and from the Getty Center, Maristella Casciato.

Where Did All the Malls Go? With Jonathan Van Ness

In the late 1990s, American malls were the place to be. Families from around the world vacationed at the Mall of America. Teens flocked to Britney Spears’ Hair Zone Mall Tour. A nine-year-old Jonathan basked in the fine fragrance mists of Juniper Breeze. Today, there are only around 700 indoor malls in the US, and more are in the midst of shuttering. What happened to these institutions? This week, Alexandra Lange joins Jonathan to discuss the rise, fall, and potential resurrection of the American mall.

The Interior Lives of Black Homes

Helen C. Maybell Anglin outside her home in the Chatham Park neighborhood in Chicago, circa 1974.

Helen C. Maybell Anglin, the self-described “soul queen of southern cuisine,” is posed on the steps of her fieldstone house on the South Side of Chicago, swathed in black mink. It is 1974, and the house, which she commissioned in 1965 from the architect Milton M. Schwartz, is as bold and glamorous as its statuesque owner, with a recessed portico, double entrance doors and a skylighted, shag-carpeted living room that’s big enough to dwarf her white baby grand piano.

Ms. Maybell Anglin died in 2009, and the house remained under family ownership until last year. Bertina Power, an author and real estate broker, was asked to give her professional opinion to someone who wanted to rehab and sell it.

“I was like, ‘I’m going to buy it,’” she said. “I have been going in and out of million-dollar houses for years and nothing moved me like this house did. I didn’t know why.”

Ms. Power is, like Ms. Maybell Anglin, a Black woman and entrepreneur just under six feet, and she has come to believe her ownership was fate. While Ms. Power did not know her new home’s history until after she stepped inside, it seems unlikely that such a house could fly under the radar now.

Ray Eames: Beauty in the Everyday

New Angle: Voice is back! We kick off Season Two with a profile of Ray Kaiser Eames.

Many know Ray Eames as the small, dirndled woman behind her more famous husband. In this episode, we uncover the talented artist who saw the world full of color, the industrial designer bending plywood in the spare bedroom, and the visionary who treated folk art, cigarette wrappers, flowers, and toys as equally valuable and inspiring. Ray brought the sparkle to the legendary Eames Office, as you’ll discover in this episode.

Special thanks to the people you’ll hear in this episode: Pat Kirkham, Lucia Dewey Atwood, Llisa Demetrios, Jeannine Oppewall, Donald Albrecht, Meg McAleer and Tracey Barton at the Library of Congress, and Alexandra Lange.

Dansk and the Promise of a Simple Scandinavian Life

Illustration by Carolina Moscoso

In the summer of 1958, the sleek, modernist Statler Hilton in Dallas hosted the presentation of the Neiman Marcus Fashion Award, an annual prize created by the department-store president Stanley Marcus and his aunt Carrie Marcus Neiman. Onstage that day were Yves Saint Laurent, fresh from the creation of his Trapeze line, which freed the waist; the children’s couturier Helen Lee, known for bright, poofy girls’ dresses; and a rather standoffish Danish housewares designer named Jens Quistgaard, plucked from the remote island where he lived, wearing antiquated knickerbockers and sailor’s shoes. Under the headline “Designing Dane, Isle’s Only Man,” a reporter for the Atlanta Journal later warned, “All you men who have wives with roving eyes, blindfold them—HURRY! The bearded Dane . . . is in town today, and the ladies are giving him looks akin to those you gave Brigitte Bardot at the movies the other night—remember?” The next day, a trifecta of models, wearing Y.S.L. sweaters and Pucci pants, posed with an ice bucket designed by Quistgaard held high like a trophy. Danish design was having its “Mad Men” moment.

In a classic American twist, the brand that Quistgaard was promoting while wearing his “customary attire of Copenhagen,” as another retailer put it, wasn’t Danish at all. Dansk originated from Great Neck, on Long Island. “ ‘Dansk’ is like when you sell vodka in the USA,” Quistgaard told his biographer, Stig Guldberg. “You use its Russian name and you kind of keep the original letters on the bottle and brochures.” Guldberg’s new monograph from Phaidon, “Jens Quistgaard: The Sculpting Designer,” seeks to disentangle the man from the brand, but the housewares consumer of 2023 treats the book like a catalogue. Yes, I would like Fjord flatware, which almost seamlessly combines teak with stainless steel. Yes, I would like an enamelled Købenstyle casserole, whose lid serves as a trivet, in brilliant red or turquoise. Yes, I would like a wenge bowl with matching salad servers, which cleverly hook on the side. Yes, I will cook and eat an Emily Nunn salad, an Alison Roman pasta, a Smitten Kitchen bake, from any of the above. The life style that Quistgaard’s design suggested—and that the Dansk founders Ted and Martha Nierenberg deftly promoted—so closely aligns with how we aspire to live now that the food-media juggernaut Food52, which acquired the Dansk brand in 2021, has begun a series of reissues and planned collaborations with contemporary designers.

On X

Follow @LangeAlexandraOn Instagram

Featured articles

CityLab

New York Times

New Angle: Voice

Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness