Edited Living: Alexandra Lange on the Pinterest Home

This essay originally appeared in the book SQM: The Quantified Home, edited by Space Caviar and produced for the 2014 Biennale Interieur in Belgium. The book gathers a number of leading authors to explore how ideas of house, home, domestic space have changed over the last hundred years.

The front door to the Pinterest house is charcoal gray, or lemon yellow, or turquoise blue. It says “Welcome” or “Hello” or “Hey, Y’All.” In winter it carries a monochrome wreath in white or red or gold. In April, rubber boots line up at its foot. In summer, it is surrounded by wisteria. In October, pumpkins pile up. Its number may be hand-painted, or pieced from tile, or set away from the wall, the better to create a crisp shadow. It likes to be photographed ajar.

The front door to the Pinterest house exhibits the characteristics of the houses collected on million-follower Pinterest boards named A Girl Can Dream and Nooks and Floored and Steal This Look. It is colorful. It has accessories. It is dressed for the season. It looks as though it is waiting for something to happen. Personifying the house, dressing it as one might a paper doll, is far from a leap: most pinners (70 million; 80 percent female; 60 percent American1) have a picture of themselves at the top of their page. Below, a series of rectangles, each with a cover image, define that portrait through pictures of (mostly) other people’s stuff. Domino magazine originated the idea of turning an outfit into a room. Pinterest proliferates it.

As media critic Rob Walker has written of visual collections in general, “It is everything we love about stuff—but without the stuff.” He theorized in 2011 that “simply pondering stuff has become a form of entertainment.” Pinterest, which launched in beta in 2010, would seem to prove his point, except for the “simply” part. Pondering stuff is indeed entertainment, but Pinterest has also become a powerful platform for sales. The types of images pinned to house boards, often further broken down into rooms, and parts of rooms, transform designing and making a house into a series of smaller and smaller purchases. It is not “from the spoon to the city” but a house built from a thousand spoons.

On Pinterest, the house becomes not an object in the landscape but a landscape, mostly interior, of vignettes. The front door. The dining table. The corner of the bed. Those vignettes are styled, by the magazines, websites or photographers who made the images, to further narrow the narrative. The moment of breakfast, with chairs pushed back and a bowlful of berries. The moment of dressing, with an outfit laid out on the duvet. And, of course, the moment of a party, with decorations layered over décor, and a still life set up on a table with pennants, cake, flowers, glasses, a living room in color-coordinated miniature. When Target asked top Pinners to develop products for their stores this year, those products were not furniture, china, or even accessories but largely disposable décor for parties. Parties are the Pinterest house’s equivalent of the Pinterest woman’s manicure: the cheapest, least-committed way to Steal This Look, down to the matching trash bags.

Pinterest collapses the difference between fashion and architecture and, more insidiously, suggests the domination of the part (or the cheap fix) over the whole. Again and again in photographs you see the same sheepskin, the same tableful of succulents, the same Target lamp. People pin these arrangements because they are accessible. The Pinterest pin is a sign of, and perhaps (as Walker suggests) even a replacement for, a purchase that may never happen. But manicures and throw pillows, necklaces and party décor are the low-hanging fruit. They are possible in a way that rainbow-painted stairs, Parisian studio windows, and open shelving with perfectly stacked and matched china are not. To keep up with the daily desires provoked by Pinterest, its users must also moderate their own desires, and figure out how they can have some small part of the Pinterest house of their dreams. Pinterest (alongside Instagram) is changing domesticity by foregrounding styling as a part of everyday life to an unprecedented degree.

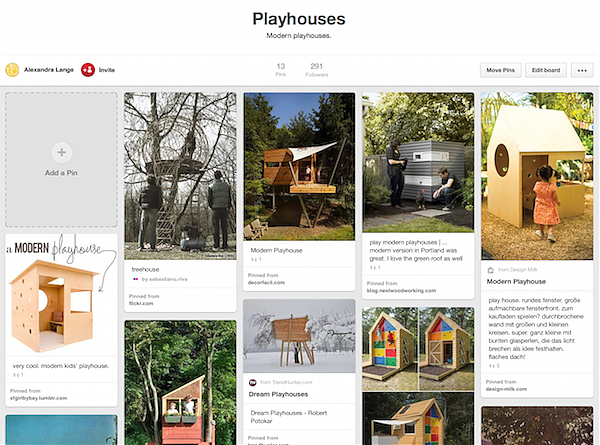

If the shelter magazine and the photo book were, traditionally, the way aspirational architecture came into our actual homes, Pinterest creates an environment in which those aspirations come down to earth. There are Architecture and Houses boards, but they are surprisingly dull. On screen, exterior shots of architecture blur together. One sharp modernist roofline becomes another. Even a shot like Julius Shulman’s iconic Stahl House view seems to be too far away. After looking at boards for a while you want to reach in and pull it closer, the better to examine the globe lamps. Famous houses show up on Pinterest in the same vintage image, pinned over and over. Where there are tens of variants on the painted floor, the Eames House (for example) gets reduced to two or three shots, some in black-and-white, that are far more boring in this context than in reality. It is easier to repin content from Pinterest than it is to import it from other locations (though style retailers, in particular, are now careful to include a button for easy pinning under their products). Thus a picture, once it is introduced on the site, tends to make the rounds.

You can choose your favorite “Eames House” from the assortment but, again, you can’t zoom in, because period photographs were designed to be consumed differently.To see what those houses of the 1950s look like optimized for Pinterest, search for Leslie Williamson. Williamson is a photographer whose two books, Handcrafted Modern and Modern Originals, translate the interiors of mid-century and designer homes into a contemporary idiom. Her photographs of J. Irwin and Xenia Miller’s House in Columbus, Indiana, bring the Alexander Girard-designed interiors up close for examination. We see the gridded wall in the master bedroom, which could be pinned to Steal This Look for either the clever arrangement of vintage crosses on pink or the gridded panels, which allow for easy rearrangement of artwork… as on Pinterest. In Irving Harper’s bathroom in Rye, New York, the wallpaper palette seems inspired by Push Pin Studios, and I can’t help wondering, given the context, where I could buy it. On Pinterest, Ray Eames’s sorted drawers of treasures, seen in top-down shots of pottery and flowers, look much more interesting than the house that surrounds them. The Pinterest platform, despite its neutral rectangles and minimal text, seems to eat space. Objects and close-ups are all.

There is nothing inherently feminine about collecting, but Pinterest has become a majority female platform because its early adopters were women, who created communities of common interests (and mutual pinning) around the home, recipes and fashion. Yet the pin metaphor is not from sewing, or jewelry, or other majority female interests, but from the architecture school pin-up (also the parent of Push Pin Studios). Pinterest co-founder Evan Sharp studied at the Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. He created Pinterest to save, share, and organize his architecture images. In 2012 Sharp told Archinect,

As an architecture student I continued to obsessively collect images … thousands of sections, renderings and photographs … and I found that it became really difficult to organize my images and refer back to them. So we built a prototype and shared it with some friends, many of whom were architects.

Organizing things is an essence of the modernist project, visible for example in the architecture and design of George Nelson, Herbert Matter, and the previously-mentioned Alexander Girard. But Pinterest makes the discovery easier; indeed, it describes itself as “a visual discovery tool.” It may make it too easy to be tasteful en masse, commodifying every constellation of choices as “this look.” When you pin or repin an image, the platform suggests more like it, so that many boards have stripes of similar ideas, a row of cabinet fronts, a row of checkerboard floors, a row of clawfoot tubs, to be compared, contrasted, and eventually moved on from. Pinterest’s endless scroll means you never have to get rid of stuff, or “stuff.” Outgrown tastes simply disappear from the bottom of the screen. George Nelson’s Storage Wall fit far more than you might think behind its plain, floor-to-ceiling doors, but it couldn’t fit years of decorating trends, specialized baking equipment, and dead plants. Pinterest means you never have to replace that wallpaper or repaint that credenza. You just need to add more pins on top. When Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum reopens in New York in December 2014, it will be testing a room-sized version of this easy-come, easy-go attitude: an “immersion room,” where visitors can choose from the museum’s 10,000-piece wallpaper collection and have

their selection projected on two walls.

The house that might result from a series of Pinterest pins would be home as a series of events, stage sets for performing particular tasks with maximum beauty. One could imagine the Pinterest grid akin to Superstudio’s Endless Monument, with white space (the disregarded halls, corridors, and paths) between the moments. It’s amusing to search for Superstudio’s gridded furniture on Pinterest, where it seems to be disappearing, replicating the platform too exactly and leaving the children posed on the benches floating in midair. Indeed, houses in America have been growing larger over the years, leaving more dead air between the functional spaces and places; perhaps Pinterest replicates that sense of intense focus followed by a lapse of attention. All-overness is not a priority, just the way things look for pictures, or for a party.

Since my first encounter with Pinterest I have been trying to plot how its commercial tendency might be turned to critique. How might we translate the way an architect thinks about a house (a plan, an organization, a path) in terms amenable to the board and the endless scroll? How might one expand the pieces of these dream homes to include the cheap (but not just the disposable) and the public (but not just the digital)? Charles W. Moore wrote of the domestic landscape of Los Angeles in the 1960s, “The new houses are separate and private, it has been pointed out; islands, alongside which are moored the automobiles that take the inhabitants off to other places.” On Pinterest, that could be translated into a House board, a Cool Cars board, and a Take Me Away board, discrete and unrelated to one another. That door, left ajar, is meant to invite your followers in to your boards. But to put the Pinterest house back together again, the pinner has to come out of that door, to think about what she is seeing rather than just how, season after season, she and her house are being seen. The freedom of Pinterest is to associate yourself with things you’ll never own, and to discard them before they have become worn-out or boring. But that freedom could feel like a trap, your choices bound by the suggestions of those who have come before. The board should feel confining—in real life, things happen between and beyond the squares on the grid.

On X

Follow @LangeAlexandraOn Instagram

Featured articles

CityLab

New York Times

New Angle: Voice

Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness