How to Fix New York City's Parks

Xinhua/Eyevine/Redux

In an ideal world, the city would robustly maintain its own seventeen hundred parks without private donations. But that’s unlikely to happen—particularly not as the park budget stretches to accommodate newer parkland on difficult marine and brownfield sites, and has to react to natural disasters like Hurricane Sandy. A tithe, however, is not the only way that private money could make its way to smaller, poorer neighborhood parks.

Why shouldn’t we all have the chance to be John Paulsons, at a hundred dollars, a thousand dollars, or ten thousand dollars a pop, giving to the parks and playgrounds in our own backyards via a network of Neighborhood Parks Conservancies? We would leverage our inherent narcissism to do some good for our daily lives, and the lives of others. The pitch: give to the park you visit every day, rather than the one you go to a couple of times a year.

"We need more museums that let us relax into knowledge"

A 1960s institution in Mexico that gives visitors space and time to wander is a stark contrast to the commodified museum experience that has become the norm.

Critics Roundtable: Pritzker Politics

Courtesy Architecture Now

The jury for the Pritzker Architecture Prize has named Shigeru Ban, Hon. FAIA, its 36th laureate, recognizing his material resourcefulness as well as his humanitarian mission as an architect. What the Pritzker Prize means to the industry changes each year with every successive selection (not to mention the architects passed over for recognition). ARCHITECT assembled four writers to break down what it all means: Alexandra Lange (Design Observer; 2014 Loeb Fellow at Harvard GSD), Christopher Hawthorne (Los Angeles Times), Mark Lamster (The Dallas Morning News), and Carolina A. Miranda (ARCHITECT).

Not Afraid of Noise: Mexico City Stories

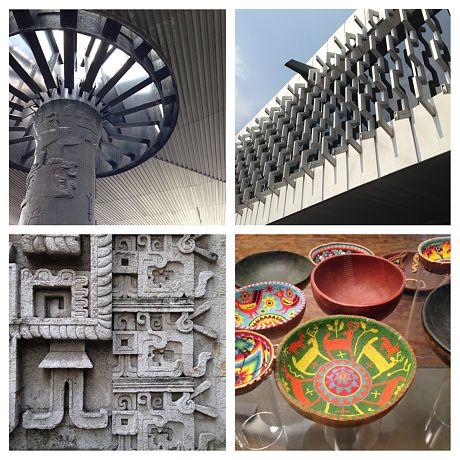

In Mexico, everyone seems to be Alexander Girard. Not afraid of color, of two colors together, of tiles and stripes, of patterns on pattern, of humble materials made noble by aggregation. The Loeb Fellowship took me to Mexico City for a week in February, and there I found the roots of Girard’s “opulent modernism” still growing. Everywhere I looked — underfoot, on the walls, over the doors — something particular was happening. I understood why he had been so inspired to collect and reinterpret Mexican precedents; more importantly I also saw Mexican designers and everyday people reinterpreting for themselves. Design with a small “d” was everywhere, reflecting a culture that seems to understand the small gestures that make a room, a building, or a city special. A church in Queretaro with checkerboard floors, a neo-classical facade, and a golden altarpiece of many doors. A museum in Mexico City with real Mayan artifacts, reconstructed Aztec facades, red-and-purple upholstery, bowls floating on plexiglass mounts. Girard distilled the elements of Mexican style, transforming them into an American modernist idiom, but it is not as if Mexican modernists weren’t doing the same. Architect Luis Barragran spotlit a golden angel with a perfectly placed skylight. Artist, architect, designer Mathias Goeritz remade the baroque icon as a simple gold-leaf square. Contemporary projects embed ceramic trees of life in Art Deco hallways, or echo the peacock circles of traditional decor in industrial spiral staircases. At the studios of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, lines of cacti march past Bauhaus silhouettes.

"How can you learn about the world in spaces without character?"

Watching the demolition of her own modernist elementary school, Alexandra Lange reflects on the increasingly generic design of schools, museums and playgrounds that resign children to “places where all they can learn are the tasks we set them.”

Premature Demolition

Wakefield Market Hall / Adjaye Associates (2008), via ArchDaily

The news last week that David Adjaye’s 2008 Wakefield Market Hall faces the wrecking ball made me start looking for a third example of what begins to seem like a trend: premature demolition. Definition: When a purpose-built structure designed by a well-known architect is destroyed at or before it reaches adolescence. The market hall: eight years. The Folk Art Museum: thirteen years. On Twitter, Philip Nobel reminded me of a third example: Bart Voorsanger’s Morgan Library addition, also demolished at thirteen. In each case, the owners of the structure have made the argument that it no longer serves its purpose: too unpopular, in the case of the market; too small, in the case of the Morgan; too “obdurate”, according to Elizabeth Diller, in the case of the Folk Art Museum.

Criticism = Love

Open Letters is a print experiment that tests the epistolary form as a device for generating conversations about architecture and design. The publication was launched in September 2013 by students at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. In preparation for the February 14 GSD symposium, What criticism?, I wrote the following letter to Tina Roth Eisenberg, a.k.a. swissmiss. It was published January 31.

Playing With Design: Fredun Shapur

In recent years, designs for children by modern masters like Bruno Munari, Charles and Ray Eames and Alexander Girard have been brought forward, their diminutive audience seen not as undermining but attractive. We should add Fredun Shapur to that pantheon of designers of winning and sculptural objects for children. Shapur’s work was produced by an international array of manufacturers, including Naef, Trendon, Galt Toys, Fischerform and Selecta, but he is best known for transforming Creative Playthings’ logo, packaging and products.

As historian Amy F. Ogata writes in the new book Fredun Shapur: Playing With Design (edited by daughter Mira Shapur), “Shapur produced toys that highlighted and challenged the child’s agency while appealing to the parents’ tastes.” This is a point Ogata made, in greater detail, in her 2013 book Designing the Creative Child: Playthings and Places in Midcentury America, reviewed here.

"It's easy to make fun of Bjarke Ingels on Instagram"

Instagram/Alexandra Lange

In her first column for Dezeen, critic Alexandra Lange argues that architects are misusing platforms like Twitter and Tumblr. “Architects need to start thinking of social media as the first draft of history,” she writes.

On X

Follow @LangeAlexandraOn Instagram

Featured articles

CityLab

New York Times

New Angle: Voice

Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness