Learning New Tricks

Three reissued Braun alarm clocks (clock of my dreams, far left)

I am one month into my Loeb Fellowship at Harvard, and I still haven’t read a book. But I am learning a great deal from sitting in on a number of classes across the university, both about pedagogy and the theory (oftentimes entire academic disciplines) behind the work I have been doing for the past ten years as a critic. I want to take this post to write it all down, both so I don’t forget, and so that I can share. (If you are interested in what I will be doing, video of my introductory talk from Sept. 13 can be found here.)

Kickstarter Urbanism: Why Building a Park Takes More Than Crowdfunding

Dan Barasch, the co-founder of the Lowline, gets calls all the time from people who think his underground “culture park” already exists. In fact, the project’s successful 2012 Kickstarter campaign was only the first step in the old-fashioned process of politicking, fundraising and engineering. A year later, a look at the renderings versus reality, and the ongoing question of what exactly the Lowline will be.

A World of Paste and Paper

Landscape architect Gary Hilderbrand’s collage Glass House Reflections II (2012)

“Composite Landscapes: Photomontage and Landscape Architecture,” Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, closes Sept. 2. Catalog is to be published in January 2014.

“Cut n’ Paste: From Architectural Assemblage to Collage City,” Museum of Modern Art, through Dec. 1

This summer two very different institutions produced parallel exhibitions on the art of collage and architecture. At the Museum of Modern Art, “Cut ‘n’ Paste” prepared a modernist history of collage, giving pride of place to Mies van der Rohe’s large photo collages, then mixing in postwar graphic design, contemporary photo-manipulation, and projections of digital renderings on a movable scrim. At the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, “Composite Landscapes” offers a similarly interdisciplinary look at the history of landscape collage, mixing working drawings and client-driven renderings with Mrs. Gardner’s travel scrapbooks and artist-made collages. Seeing them both suggests common themes as well as opposed approaches to envisioning and embracing landscape.

Architecture's Lean In Moment

From left: Ray Eames; Denise Scott Brown; Jeanne Gang

“Women are the ghosts of modern architecture, everywhere present, crucial, but strangely invisible,” writes historian Beatriz Colomina in “With, Or Without You,” an essay in the Museum of Modern Art’s 2010 catalog, Modern Women. “Architecture is deeply collaborative, more like moviemaking than visual art, for example. But unlike movies, this is hardly ever acknowledged.” Colomina goes on to chronicle the history of modernism’s missing women, acknowledged, if at all, as working “with” Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, Alvar Aalto, or Charles Eames. To put yourself in the shoes of Lilly Reich, Charlotte Perriand, and Aino Aalto, simply watch the cringe-worthy video of the Eameses on the Home show in 1956, Ray introduced as the “very capable woman behind him” who enters after Charles has bantered with host Arlene Francis.

This spring, these ghosts came back to haunt us: Arielle Assouline-Lichten, a student at the Graduate School of Design at Harvard, read excerpts from an interview with Denise Scott Brown in which she mentioned her own absence from partner Robert Venturi’s 1991 Pritzker Prize. “They owe me not a Pritzker Prize but a Pritzker inclusion ceremony,” Scott Brown said. “Let’s salute the notion of joint creativity.” Assouline-Lichten had just relaunched the Women in Design student group at the GSD with Caroline James; she emailed James, they drafted a petition, and three hours later the call for recognition of Scott Brown by the Pritzker Committee was live at Change.org. By late May the petition had more than 12,500 signatures, including nine Pritzker recipients: Robert Venturi (“Denise Scott Brown is my inspiring and equal partner”); Rem Koolhaas (“an embarrassing injustice”); and Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron. Colomina wrote simply, “We are all Denise.”

Nevermind the Masterpiece

Broken Umbrella (photo by Lauren Manning and Veronica Acosta)

To assemble the “Masterpieces of Everyday New York” which currently fill the Sheila C. Johnson Design Center at Parsons The New School for Design, curators Margot Bouman and Radhika Subramaniam asked their colleagues to select objects that brought their city to life. Inspired by the popular book and radio series, A History of the World in 100 Objects, they then used these objects to present 65 stories of different times, places, lives and deaths in the city. Each faculty member contributed a text on their choice, some personal, some academic. In the spare, concrete-floored gallery at Parsons, different objects communicate across the room, and you can move in almost any direction and pick up a narrative thread. The exhibition kicks off a new curriculum for first-year design students that will use New York’s museum collections as text, rather than a textbook, and will begin with the course “Objects as History: From Prehistory to Industrialization.”

How To Unforget

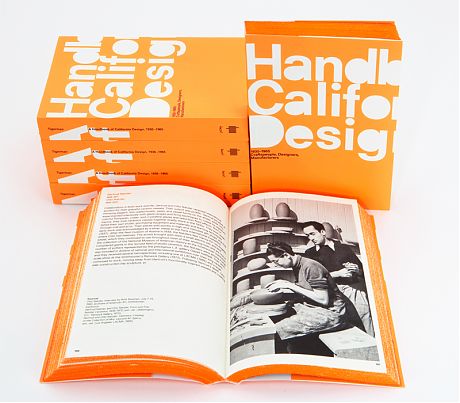

A Handbook of California Design, 1930-1965: Craftspeople, Designers, Manufacturers (Los Angeles County Museum of Art and MIT Press), edited by Bobbye Tigerman (via LAMA)

A few weeks ago Despina Stratigakos published a vigorous call to arms for historians at Places, “Unforgetting Women Architects: From the Pritzker to Wikipedia.“ She writes,

History is not a simple meritocracy: it is a narrative of the past written and revised — or not written at all — by people with agendas. Forgetting women architects has also been imbedded in the very models we use for writing architectural history. The monograph format, which has long dominated the field, lends itself to the celebration of the heroic “genius,” typically a male figure defined by qualities such as boldness, independence, toughness and vigor — all of which have been coded in Western culture as masculine traits. Moreover, the monograph is usually conceived as a sort of genealogy, which places the architect in a lineage of “great men,” laying out both the “masters” from whom he has descended and the impressive followers in his wake. For those seeking to write other kinds of narratives, the monograph has felt like an intellectual straitjacket, especially in contemplating the lives and careers of women who do not fit the prescribed contours.

Stratigakos’s essay serves as a digital call to arms, to get more women into Wikipedia and other online encyclopedias so that (at minimum) their existance cannot be called into question. But digital means are not the only ways of unforgetting, and when I finally picked up the neon orange A Handbook of California Design, 1930-1965: Craftspeople, Designers, Manufacturers, published this spring as a companion and follow-on to the 2012 exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, “Living In A Modern Way,” it seemed like another means of unforgetting, one which takes on the monograph form by suggesting that a group biography, emphasizing connections, collaborations and a sort of collective design advancement, might do just as well.

Is Cake Art?

Last winter, the Museum of Modern Art announced the acquisition of fourteen video games, including Pac-Man, Tetris, Myst, SimCity, and Portal. This set off a predictable high-culture call-and-response. In the Guardian, Jonathan Jones defended masterpieces by Jackson Pollock and Pablo Picasso against their new neighbors, arguing that the art is a personal vision, so multi-player games, and the interactive experience, can never be. James Turrell would beg to differ. But it was a stupid question anyway: the games were acquired by the Architecture & Design department, where many creators, and many users, are part of the typical creative process. The step from the iPhone to its apps is less of a leap. The faux controversy did spawn this excellent TED talk, where MoMA curator Paola Antonelli explains “Why I brought Pac-Man to MoMA.”

A less obvious question, raised by baking with and reading Modern Art Desserts, from Blue Bottle Coffee pastry chef Caitlin Freeman, is, Is Cake Art?

Light and Space and Curves

Instagram by ebatesdotcom

In his 1959 review of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum for The New Yorker, Lewis Mumford ends with a suggestion that may be his idea of a joke. “I can think of only one way of fully redeeming [Frank Lloyd] Wright’s monumental and ultimately mischievous failure—that of turning the building into a museum of architecture,” he quips. Yet each time the Guggenheim allows an artist to take over the building’s central rotunda, the truth in the witticism is revealed: what looks best in Wright’s building is work that refers to, sets off, qualifies, or amplifies the architecture. It’s almost never architecture itself. Zaha Hadid’s angles clashed with Wright’s curves (2006). Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggan’s Soft Shuttlecock (1995) merely accessorized them.

James Turrell’s Aten Reign (2013), installed in the rotunda as part of a multi-city retrospective, manages to defy and celebrate the building all at once. As Turrell said at the exhibition’s opening, “Richard [Armstrong, the Guggenheim’s director] was wondering for a while if this was something Frank would like.” A pause like a shrug. “This is an art museum, we are going to put art into it.” At that, he has done a spectacular job.

Every Little Thing

I spent part of last weekend at the Michigan Modern symposium, giving a talk on Alexander Girard, a decade-long inhabitant of the tony Detroit suburb of Grosse Pointe and a longtime designer for Zeeland’s Herman Miller. I heard talks about roadside architecture, the origins of the shopping mall, and the origins of Herman Miller’s ongoing design excellence. Though designers from Detroit (and former furniture capital Grand Rapids) often took their talents to Los Angeles, New York, Santa Fe, all of the participants struggled to define what these famous and not-so-famous names learned from Michigan. I thought the answer was all around us, where we ate, where we listened, where we walked.

Le Corbusier At Moma

Model of the roof terrace of the Unité d’Habitation, Marseille (1946-52). Credit: Fondation Le Corbusier/ARS/ADAGP/FLC.

The psychological center of the Museum of Modern Art’s giant Le Corbusier retrospective, “An Atlas of Modern Landscapes,” is located in the second-to-last gallery. There, taking a few steps in any direction, it’s possible to see many of the Swiss architect’s qualities represented, for better and for worse.

His ardent explanations, for one, which are embodied by wall-size drawings made during lectures on his 1935 trip to America, describing what’s wrong with New York skyscrapers (“not big enough”) and how the traditional peak-roofed house must be replaced by a house on stilts. His attention to reputation, represented by a 1947 collage laying sole claim to the design of the United Nations complex, sketch by sketch. His make-no-little-plans ambition, realized (for once!) in the design of Chandigarh, the new capital of Punjab, in India, seen in plan, drawing, film, photograph, and an arresting six-by-eight-foot wooden model, built by a cabinetmaker and hung on the wall like sculpture. His lifetime exploration of materials, which took him from the delicate hardwood veneer of his mother’s writing desk, designed in 1915-1916, to the curved, chromed tubing of his famous 1928 chaise, or from the white stucco walls of the modernist icon Villa Savoye (1928-31) to the béton brut (rough concrete) of his apartment tower, the Unité d’Habitation in Marseilles (1946-52).

On X

Follow @LangeAlexandraOn Instagram

Featured articles

CityLab

New York Times

New Angle: Voice

Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness