That Personal Touch

In late May, News Corp. released a new logo, seen above, to herald the split of the company into two parts: News Corp. (newspapers and publishing) and 21st Century Fox (entertainment). The logo release was something more than that too: described as being derived from the handwriting of News Corp. founder Rupert Murdoch and his father Keith, the logo seemed to indicate a return to family control, and that Rupert was to be literally hands-on as the corporation shook off its scandal. In the Guardian, Creative Review’s Mark Sinclair noted, “In the era of digital text, handwritten lettering can appear honest, candid even.” Note the can because this artless logo immediately seemed like something else. First, the handwriting of two people cannot be candid. It’s been manipulated, apparently to create a better press release narrative. If you don’t like Rupert, remember his father. It’s also undistinguished. That initial N could never stand as a part for the whole logo, as anyone could write it. And the blobby ends of the N and P suggest Sharpie origins, the bleeding when you let the pen linger too long on your packing box. The black and white looks cheap, which may also have been the point, after a 20th century of geometric symbols and shiny gradients. Scripts are supposed to signal nostalgia, personal connection, with-love-from-me-to-you. But when anyone can make their handwriting into a font, has script lost its meaning?

Praise the Partner(s)

Below is an essay published in Architecture d’Aujourd’hui No. 395, on the topic of the current petiton for the Pritzker Prize committee to recognize the work of Denise Scott Brown, and the larger issues this raises for the practice of architecture and the giving or prizes.

So let’s salute Denise Scott Brown because she deserves it, and because she may indeed be, as Martin Filler put it in the New York Review of Books in 2010, “The World’s Foremost Female Architect.” But let’s not forget the second part of the quote. What needs to shift in architecture is more than making a place for women — it’s making a place for partners. For acknowledging strengths and weaknesses and pretending neither that one guru does it all, not that we can have it all.

Home Improvement

Last week, the editors of The Wirecutter launched The Sweethome, extending their no-nonsense, one-recommendation-per-category approach from tech products to the home. I’ve been a fan of The Wirecutter since its launch, and purchased several items on their recommendation. But I find myself in the market for towels, toaster ovens and toilet paper more often than I am for printers and phones, and the choices for recommendations more limited. The combination of the two categories also fulfills a digital need I spotted long ago, and links to a number of discussions previously held on Design Observer. Below is a short interview with Sweethome editor Joel Johnson. But first, a little background on the issues at hand.

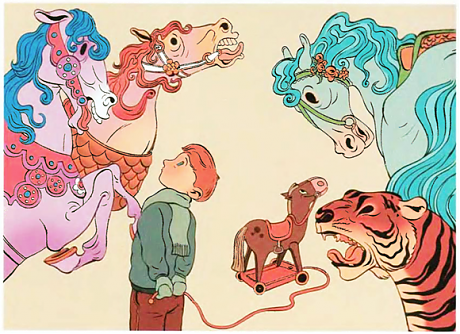

Why Wooden Toys?

Illustration by Zohar Lazar

“Love LEGO but hate plastic?” asked Apartment Therapy in March, just one of more than a dozen design blogs to feature wooden Lego blocks, made by Mokulock, this spring. Described as “handmade” and “all-natural,” the eight-stud-size blocks have clear visual appeal, in the minimalist Muji way, and come packaged in a brown cardboard box, with an unbleached cotton sack for storage. One commenter dreamed of brick and concrete varieties, as well, to teach children about real building materials.

But beyond the blocks’ good looks lurked some very basic questions of function. Design Boom noted a product disclaimer that “the pieces can warp or fit together imprecisely due to the nature of the material in different temperatures and scale of humidity.” Another commenter brought up sustainability, “considering the sheer number of Lego blocks produced a year.” Are Legos even Legos without the universal snap-together property? Do toys need to be as artisanal as our food? I understand why my child would want to make his own toy, but does someone else need to do it for him? And why wood?

The Fork and the World: Design 101

If you had to explain design to the uninitiated, where would you start? With a technological object you could hold in your hand? With the history of the word “design”? With tales from the literal trenches, where, in 246 BC, standardized bows and arrows allowed Ying Zheng to become the self-styled “First Emperor of China”? Or would you begin and end closer to home, exploring the design histories of the kitchen drawers and appliances you see before you, from fork to spoon to spit?

Dream Weaver

When I wrote about the figure of the knitting architect in February, inspired by Maria Semple’s novel Where’d You Go, Bernadette, little did I know that a panoply of knitted, woven and recycled work would soon be on display in New York … all under the rubric of art, but definitely spatial and challenging. El Anatsui’s sinuous works at the Brooklyn Museum, which play with one’s sense of weight and material, Orly Genger’s Red, Yellow and Blue in Madison Square park, walls of crocheted rope that snake through the park, and, most modest in scale, the first New York show in 50 years of the work of midcentury sculptor Ruth Asawa, who wove forests, anemones and orbs out of metal wire. One of Asawa’s largest works, known as Untitled (S.108, hanging, six lobed, multi-layered continuous form within a form), was auctioned by Christie’s, the organizers of the exhibition “Ruth Asawa: Objects & Apparitions”, on May 15 for $1.4 million, four times its low estimate. (I posted a few of my own photos of the exhibit on Tumblr; Christie’s also made a video.)

Anxiety, Culture and Commerce

One of the earliest design shows at the Museum of Modern Art was called “Useful Object Under $5.” There’s not a lot of anxiety, or pretension, in that title. The exhibit opened at the museum in 1938 and then traveled to ten cities. The press release states that the wares include an aluminum tea kettle, a red rubber-covered dish drainer, a traveling iron, stainless steel knives, a shower curtain, a fur hangar. And that several items came from the five and dime.

Donald Judd's House

Donald Judd with students, 1974. Photograph: Barbara Quinn/Courtesy Judd Foundation Archives.

There’s a shovel attached to the wall on the fifth floor of 101 Spring Street. “Why didn’t they keep that downstairs?” asked a recent visitor.

“It’s a Duchamp,” the guide replied.

It’s like that on every floor of the artist Donald Judd’s former home and studio. There’s a Stuart Davis in the baby’s room and a Duchamp bottle rack up in the sleeping loft. A 1967 Frank Stella protractor series painting has pride of place on the fourth floor, used for entertaining, but a drawing by Stella hangs against an (attractively) decaying wall in the stairwell, at home with the African masks. Judd surrounded himself with design that suited his aesthetic as well as his art. The high chair is Thonet. Zigzag chairs by Gerrit Rietveld pulled up to his own table. Czech glassware tucked into the clever, deep well of another table. The first thing Judd saw every morning: a 1969 Dan Flavin neon sculpture, chasséing the length of the room, tubes of red and blue light framing his western view.

Just Sew It

Search “toddler peasant dress,” and the first picture that pops up is of argyle fabric, cut in four pieces, laid out in the shape of a outfit. Little Bean Workshop first posted this illustrated tutorial in 2010, but as its current presence atop Google Images indicates, the appetite for straight-seam, no button, easy-on dresses for the under-four set continues unabated. That’s how I found it one evening, when I discovered a rectangle of Indian cotton in my drawer of textile scraps and realized, for the first time in ages, that I just wanted to make something.

Beyond Gorgeous

Earlier this month I had the pleasure of checking another famous modern house off my lifetime list: the J. Irwin and Xenia Miller House in Columbus, IN, about which I first wrote in 2006. The house was opened to the public in 2011, when it became part of the Indianapolis Museum of Art, and I published this account of its creation and significance then. Having studied the house for different projects over the years, it did not surprise me in person. The colors are as vibrant, the details as clever, the combination of lushness, personality and modernity as striking as I imagined. One material choice I never understood was the dark slate panels on the exterior: why not just make it white? But when you see the house in person, you understand the single-story facade as a dark band, designed to be recessive. The slate blends with the glass, which is reflective and backed with fretted drapes, many made by Jack Lenor Larsen, with gray and metallic threads. The roof and the surrounding patio read as white, flating planes. You pass through the dark band and enter a house that is all white, expansive, dotted with color. The contrast is extreme and unlike that of outside/inside in a glass house.

On X

Follow @LangeAlexandraOn Instagram

Featured articles

CityLab

New York Times

New Angle: Voice

Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness