At Age 14, No Stranger to a Steal

On the Internet, no one cares that you’re 13. That’s what Henry Kilpatrick discovered when he started his vintage-furniture retail site, Magic City Finds, in September 2011, at the dawn of his teen years. Mr. Kilpatrick, who is now 14 and lives in Birmingham, Ala., had no idea who Herman Miller was when he plucked a fiberglass armchair from his grandmother’s storage space, but one online search later, he knew he had a find. He plowed the $75 he made on that initial sale, along with some birthday money, back into furniture bought at estate sales and off Craigslist, including 20 more Eames chairs, which cycled through his parents’ garage. He mostly works on the weekends, as it is “tough to do schoolwork and business, and schoolwork comes first,” he said.

Architecture Without Signs

I love graphic design. I understand the importance of way-finding systems. I own a label maker. I wish I had a color-coded closet. But architecture needs to work without words. The building should point your way to its entrance without an arrow. Finding the visitors desk should not require a level change. If everyone is putting their feet on the wall, the bench is too close.

Dreams Built and Broken: On Ada Louise Huxtable

Ever since 1963, the year she became the first architecture critic for The New York Times, Ada Louise Huxtable had been warning of the tragedy in store when the old Pennsylvania Station would be razed to make way for Madison Square Garden. The tragedy came three years later when the wrecking balls started battering the fifty-six-year-old building, which was designed by McKim, Mead & White and had been a worthy West Side pendant to Grand Central Terminal, now celebrating its centenary. The station’s vaulted, skylit concourse, travertine interiors and by then soot-stained murals of the Pennsylvania territory were reduced to rubble and dust. As Huxtable wrote in her obituary for the building, published on July 14 of that year, Penn Station “succumbed to progress this week…after a lingering decline. The building’s one remaining facade was shorn of eagles and ornament yesterday, preparatory to leveling the last wall. It went not with a bang, or a whimper, but to the rustle of real estate stock shares.”

What It Costs (to Buy a Bench, to Extend a Curb)

On Saturday afternoon, after dropping my son at a birthday party, I voted. For the first time in my experience it wasn’t for a person, but for places, technology and trees. In 2011 my New York City Council member, Brad Lander (a former housing advocate), decided to launch participatory budgeting in his distrct, allowing community members to vote on how to spend $1 million in discretionary funds in our neighborhood. We were each allowed to vote for five projects, which ranged in price from $350,000 for safety improvements to the fast-moving street at the end of my block, to $40,000 for new benches in Prospect Park. Transit and kids garnered the lions’ share of proposals, with three environmental projects in the middle. I suspect that in the wake of Superstorm Sandy 2013’s ballot will be festooned with projects focused on drainage, runoff and soft infrastructure.

How To Make A Great Kids’ App

In ev’ry job that must be done

There is an element of fun.

You find the fun and snap!

The job’s a game.

In the 1964 musical film “Mary Poppins,” all it takes is a snap of the nanny’s fingers and the toys march into the toy box, the clothes fold themselves, and the covers ripple up the beds. What the song argues, and the movie fails to show, is that for kids housework is indeed a game. My daughter likes nothing more than emptying the dishwasher (and then wheeling the lower basket around the room); my son stole the mini-broom from me almost every time that I took it out. Toca House, an iOS app from the Swedish digital play studio Toca Boca, understands the fun of these adult jobs: players scroll up and down a tall, narrow house, selecting first a room and then a task. Clean the windows? Move your finger to rub a cloth against the glass until it shines. Dry the clothes? Lift each shirt or pair of socks and pin it to the clothesline. On the Toca Boca site, the play designer Erik Wahlgren explains, “To small children housekeeping is novel, in their eyes it’s an act of making things nice.”

Portlandia + Timelessness

A couple of weeks ago designer Frank Chimero posted a rant on his blog about “timeless” design. In a nutshell: what we call timeless today is a rough approximation of mainstream work in 1962, the work we see from that era looks good because time and taste have already separated the wheat from the chaff, and what’s so great about “timeless” design anyway?

Some might say that this blog’s design has some “timeless” qualities. I will let you in on a secret: I am lazy. I want to make as few decisions as possible, but I want those choices to be good ones. I don’t add cruft, because I’d have to make the cruft so that I could add it. And then I’d have to decide where it would go, when all I really want to do is find that chimp with the ice cream cone and hang out with him.

I’d been thinking about this post because I agree with him. I’m thrilled with our current definition of “timeless” design, but I know that is because I am well aware my taste is straight out of 1962. The process of writing the Design Research book was one of discovering that the things I grew up with, many of which I bought again for my own house, were all for sale at D/R, and thus, what I thought was idiosyncratic was actually collective.

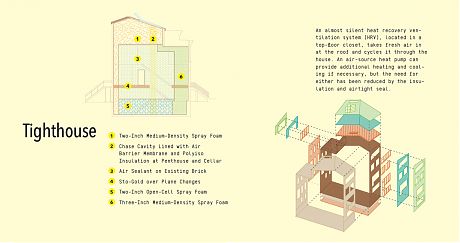

A Sustainable Brownstone Transformation In Brooklyn

The street facade of New York City’s first certified Passive House, known as Tighthouse, is clad in pale gray stucco, sculpted with a few historic-looking details. But, if you knock on that wall, it sounds hollow: The stucco is merely the outermost layer in a 20-inch-thick insulated sandwich. The original brick is buried deep inside, where it can do no harm—via chinks, cracks, or settling—to the supersealed box this 19th-century, 3,120-square-foot Park Slope house has now become. The cornice, too, is a lightweight contemporary replacement: a hollow fiberglass shell mimicking a wood original.

The smooth, low-maintenance surfaces are a far cry from the derelict three-story row house designer Julie Torres Moskovitz first saw in 2009. The brownstone’s front facade was pocked and cracked, the back wall was falling apart, and the interior left a warren of mystery rooms (including one lined with a one-way mirror). The owners, a young couple just starting a family, weren’t daunted by the damage because they wanted a clean, modern renovation to showcase their art collection. “The owners say they don’t like anything organic,” says Torres Moskovitz. “Only concrete and steel.

Instagramming Around Australia

It’s been quite a while since architecture made my jaw drop. But it did, literally, as I walked down Swanston Street in Melbourne ten days ago. There, in the space of a few blocks, is a collection of buildings so bright, so prickly, so merchanical, so textural that they create their own context. RMIT University, a school of design and technology, has spent the last 20 years hiring local architects to design academic buildings of a type hard to imagine on any of the campuses I’ve studied on. The first on Swanston was Building 8 by Edmond & Corrigan completed in 1993. Its plastic, pastel interiors were described to me as being modeled on an Italian hill town, like the university work of Charles Moore. Its exterior, with tile patterns and palm tree cutouts, part of the diaspora of the ideas of Venturi & Scott Brown, with whom Peter Corrigan studied at Yale in the late 1960s. Edmond is Maggie Edmond, whom Wikipedia says is “probably the nation’s foremost female architect.” Building 8 was joined in 1996 by Storey Hall by ARM Architecture, then in 2011 by Building 22, also ARM. Across the street, a spiny commercial tower calls to the latest edition, Lyons’ Swanston Academic Building, which opened last year and is variously known as the Pineapple, the Porcupine and the Cheese Grater. My own photos of all of these, plus the Cheese, Sean Godsell’s willfully monochrome (yet still ornamented) RMIT Design Hub are in the slideshow below.

After the Museum: The Tumblr

I’ve written several times about Tumblr as a platform for everyday interactions with museums, archives and other collections of visual and historical artifacts (see here, here and most recently here, in “Shopping With Sandro”). One of the benefits of museum Tumblrs and similar projects like the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum’s Object of the Day, is the potential they have to surface items in the collection that have not been exhibited for years, to hold them up next to more current and popular objects, and see what connections happen. The Tumblr can be like a sketch of curation, cheaper and less consequential than an exhibit; or deeper and wonkier on a particular, even personal topic.

Plain or Fancy?

I tried, really I did. But with a vintage Braun coffeemaker and Muji soap dishes, was there any chance I would prefer the items on the Fancy side of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s tiny new exhibit, “Plain or Fancy? Restraint and Exuberance in the Decorative Arts”? Not really.

I stood in front of the Dutch seventeenth-century nautilus cup—a pearly shell the size of a softball, surmounted with a golden Neptune riding a whale, out of whose mouth Jonah emerges (must not have been against the rules to mix mythologies). I wished the mount away. How much more beautiful would the shell be, how much easier to see its harmonic proportions, without all that glitz? For its owner, however, the unadorned shell didn’t show: the shell, like its neighbors made of stones of sardonyx and jasper, was a precious material without natural glamour. The lily needed gilding in order to demonstrate its worth.

The “Plain or Fancy?” exhibition, which is culled from the museum’s permanent collection of European decorative arts, begs viewers to stand in front of its forty objects and engage in similar internal disputes. Lists of synonyms for plain—masculine, severe, dull—and fancy—flamboyant, ostentatious, vulgar—are painted on walls that are gray and pink, respectively. Both the adjectives and the color choices seem a bit pushy, like putting words in the visitor’s mouth.

On X

Follow @LangeAlexandraOn Instagram

Featured articles

CityLab

New York Times

New Angle: Voice

Getting Curious with Jonathan Van Ness